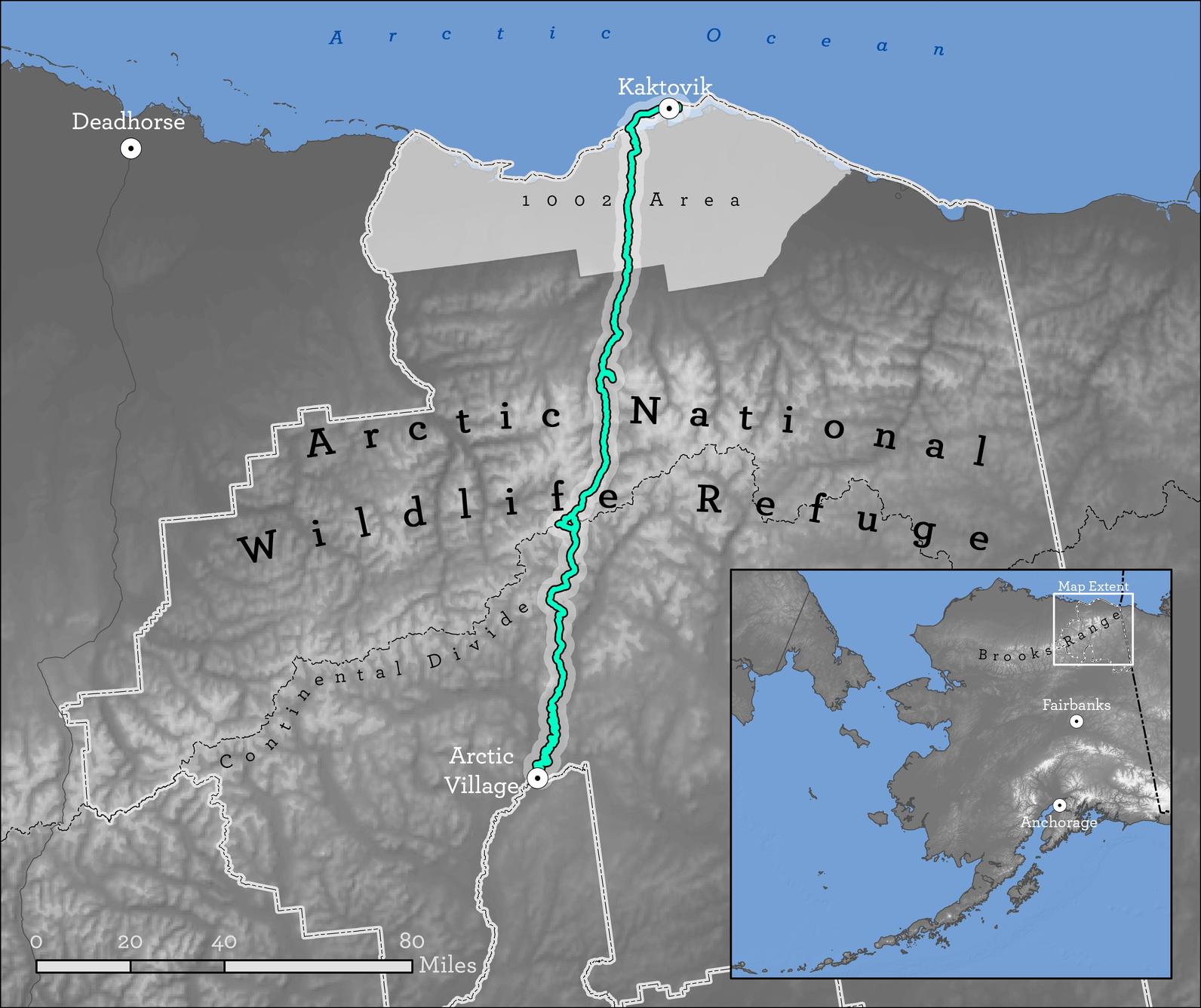

This is the first in a series of blog posts by Ben Sullender, Spatial Ecologist at Audubon Alaska. Throughout the series, Ben shares his experiences and reflections from his recent 14-day, 200-mile adventure in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. He was joined by Sarah Glaser. The two of them set out from Arctic Village, hiking and paddling their way to the Arctic Ocean.

We knew we were taking two big risks by running Arctic rivers so late in the season, and already we’d struck out on the first of those. We were still miles from the Arctic Ocean, but already the water levels were too low to float. We’d given up on trying to choose sufficiently deep channels as the Okpilak River braided wider and wider. The sustained headwind meant that paddling in the brackish lagoon next to us would be useless. So we resigned ourselves to trudge on foot across the swampy tundra. Overhead, the sky was alive with flocks of Snow Geese and Brant sweeping past. Every step seemed to flush another several dozen birds as we towered above the low-relief tundra. We leaned into the intensifying wind, watched dark clouds gather on the horizon, and slogged onwards.

As tired as we were, we were silently transfixed on the same thought, our other serious risk: encountering a polar bear. We knew that our timing, arriving on the coast in the last few days of August, would bring us right into the most dangerous time of year for polar bears. In the summer, polar bears are generally out in the Beaufort Sea, hunting seals from sea ice platforms. In the fall, these bears move to the coast to scavenge bowhead whale carcasses. In between seasons, when the sea ice recedes too far from the safety of land, bears swim back to shore and hunker down, fasting until whales arrive. During these lean weeks of transitioning food sources, I’d heard of bears making overland foraging trips. I hoped that they wouldn’t be foraging for us.

We finally made our way to the edge of Arey Lagoon. No more freshwater to follow. Between the broken icebergs out at sea, I noticed an out-of-place shape on the horizon, and quickly grabbed my binoculars. A jolt ran through me. I grabbed Sarah’s shoulder, and pressed the binoculars into her hand, pointing at the edge of the barrier island.

It was the boat! I hoisted my paddle above my head and swung back and forth to get its attention. Thanks to the tireless logistical efforts of a friend back in Anchorage, and back-and-forth inReach texts to pin down location and timing as our route solidified, we’d coordinated a boat pickup from a Kaktovik-based polar bear guide. We didn’t want to risk the day or two it would take to hike from the Okpilak River to Kaktovik along a network of barrier islands, which in our minds were teeming with ravenous polar bears. Instead, we got in touch with Bruce, a polar bear guide with an impressively seaworthy boat that he used to take tourists bear-viewing. Bruce’s busy season was picking up as the bears came back onshore, but he had a long enough break in his schedule to head out and pick us up. We’re glad he did.

This was the culmination of our traverse of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a 14-day, 200-mile adventure. We began in Arctic Village, a small community in interior Alaska, and finished in Kaktovik, on the Arctic Ocean. Arctic Village is geographically separated from Kaktovik by the Brooks Range, hydrologically separated by the Arctic Divide (the central line that divides into watersheds that flow to the Pacific and watersheds that flow to the Arctic Ocean), and culturally separated by available subsistence resources (the Arctic Village Gwitch’in rely on caribou, and the Kaktovik Inupiat primarily harvest marine mammals). Our goal was to survey the range of landscapes that the Arctic Refuge represents: the boggy boreal common to interior Alaska, the barren, precipitous Brooks Range, and the Arctic coastal plain teeming with wildlife.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (known by conservationists as the Arctic Refuge, or simply, the Refuge) is distinctly wild in a state known for its distinctive wilderness. The Refuge encompasses 19.3 million acres, making it the largest protected area in the United States.

However, the Arctic Refuge’s protected status is under threat. As a part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the U.S. Congress passed a provision aimed at exploiting undiscovered oil in a portion of the Refuge. Senator Lisa Murkowski tacked on the oil-and-gas-leasing language to the tax bill in order to avoid a regular senate vote, which, given the widespread opposition to drilling in the Refuge, likely would not have passed in open debate. Instead, by being hidden as one short paragraph in the 505-page tax bill, the issue of drilling the Refuge was only subject to a simple majority vote. This underhanded approach succeeded where more overt efforts have failed over the past 40 years.

Although the lands opened to drilling (called the 1002 Area) cover “only” 1.5 million acres, they encompass the Refuge’s entire Arctic coastal plain. Simply put, the Arctic coastal plain is the beating heart of the whole ecosystem. Due to a combination of suitable physical factors and productive vegetation, a huge range of wildlife return to the 1002 Area as the focal point of their long-distance migrations. Parturient (pregnant) cow caribou in the Porcupine caribou herd almost always calve (give birth) in this area. Shorebirds and waterbirds fly thousands of miles to breed and nest on the Arctic coastal plain. Given the certain (e.g. disturbance, loss of habitat) and likely (e.g. oil spills) negative impacts of oil development on wildlife, oil extraction, and wildlife conservation are not compatible in this area.

The wilderness character of the Arctic Refuge also has significant importance for a different type of wildlife: human adventurers. The dozen or so rivers that run from the eroded summits of the eastern Brooks Range down to the Arctic Ocean provide unprecedented recreation opportunities, from backpacking and hiking, to packrafting and floating, to mountaineering and skiing, to fishing and hunting. These experiences reward people with a lifetime of inspiration. There is no other place on earth like it.

The American Packrafting Association, in collaboration with Alpackaraft, have taken up the initiative to speak up on behalf of these recreational values and move to protect our ability to experience these public lands. Alpackaraft created two custom packrafts, named Mardy and Olaus, after the Muries, the original Arctic wilderness power couple. They’ve lent these boats out to folks to take them on journeys celebrating the wilderness experience in the Refuge, and to collect stories that showcase the importance of these public lands for people from all over the world. They were gracious enough to loan us Ms. Mardy, a beautiful blue Yukon Yak with a whitewater deck, for our trip.

In the coming weeks, follow along with me as I recap some highlights from my journey. I’ll post a series of stories and photos to this blog to help convey what this spectacular place is like. Hopefully, they’ll serve as an inspiration in helping with the greater conservation effort required to help us protect this wild place in the coming months and years.

Read all of the blog posts in this series:

Arctic Refuge Ramble: Ben’s Journey across the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Arctic Refuge Ramble: Arctic Village

Arctic Refuge Ramble: Into the Wilderness