Taashuyee-Chookan.aani, or the Mendenhall Wetlands complex, has several things going for it. It’s a scenic public refuge, a host to an abundance of species, and a globally recognized Important Bird Area—the highest honor on the IBA scale.

But it’s also one of the most threatened IBAs in Alaska. For starters, the wetlands are literally surrounded by Juneau, the state’s third-largest city, which has roughly 32,000 residents but also sees up to 1.6 million visitors annually. Then another threat is the heavily debated Juneau Douglas North Crossing—a major development project that has been looming since 1984 and could cut through the wetlands.

Yet many folks—working groups, conservation organizations, and residents—are working carefully to defend the wetlands while not coming off as anti-development. The solution, though, could come in the form of one proposed crossing location—Salmon Creek.

What and Where is the Mendenhall Wetlands Important Bird Area?

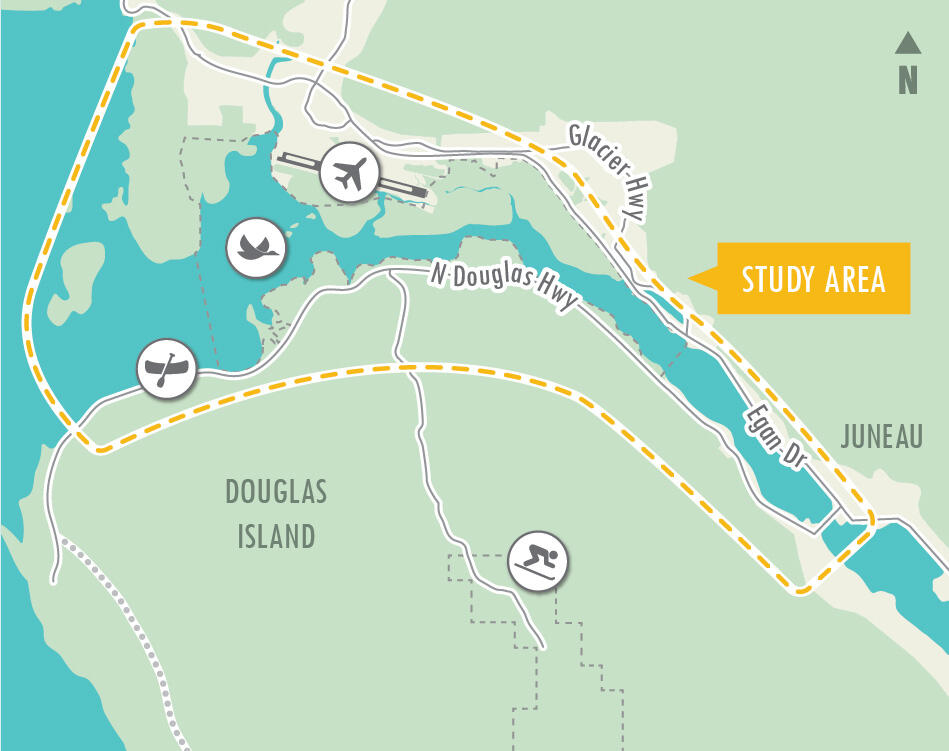

The 4,497-acre Taashuyee-Chookan.aani/Mendenhall Wetlands is located in Juneau, Alaska, in Áak'w Ḵwáan Territory on the ancestral lands of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples.

To drop science for second, according to National Audubon Society, the Mendenhall Wetlands Important Bird Area (note: this IBA report lists all National Audubon Society sources and citations for the data outlined in this section) has the third-greatest acreage of vegetated tidal salt marsh of all estuaries in Southeast Alaska. It is widely acknowledged to be one of the key migratory waterfowl and shorebird stopover locations of coastal Alaska and is of outstanding value to waterbirds, as well as certain grassland and wet-meadow songbirds and raptors.

A total of 230 species of birds have been documented to occur on the Mendenhall Wetlands, representing 77% of the 300 bird species seen in the Juneau area from Taku Inlet to Berners Bay and 69% of the 335 bird species seen for all of Southeast Alaska between Dixon Entrance and Yakutat.

This is probably why Audubon designated it a global Important Bird Area in 2007. The key word here is “global.” IBA priorities come in tiers—first state, then continental, and finally global, the highest.

But Audubon isn’t the only one who sees the wetlands as a worldwide prize.

Margaret Custer, Executive Director of Southeast Alaska Land Trust (SEALT) since 2021, says, “The land trust recognized from its inception in 1995 that Taashuyee was a vital link between Southeast Alaska and the rest of the world, providing migratory and resident bird habitat in pristine tidal wetlands.” Custer is also the Chairperson of the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge Citizen Advisory Board.

Within this complex is the 3,786-acre Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge (Refuge) managed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). Most of the Mendenhall Wetlands are owned by the State of Alaska. A smaller portion falls under the City and Borough of Juneau (CBJ) and other portions are privately owned. (All of this sits within the 17-million-acre Tongass National Forest—the country’s largest national forest and forest carbon sink, holding approximately 20% of all carbon stored in the United States National Forest system.)

So, if the wetlands are both a state Refuge and a global IBA, it should be off the table for development, right? Well.

“Keep in mind with IBAs, it's not a protected land status at all,” says River Gates, Shorebird Conservation Manager with Audubon Alaska and Pacific Shorebird Conservation Initiative Coordinator with National Audubon Society. “We basically say that they're really important ... but some are just wetlands on the side of the road that are in the public domain.”

And that’s why we’re here, discussing how a major development project could cut through a Refuge and IBA. But often, the issue gets dismissed as a hyper-local thing, a divisive Juneau-only topic, but it could have statewide, even worldwide, impacts.

“This is not a matter of a few acres,” says Matt Robus, the former Director of the Division of Wildlife Conservation with ADF&G (and now on the board of SEALT and member of the Mendenhall Wetlands Study Group). “This is a matter of a really important area being jeopardized.”

How Is the Refuge a Really Important Area?

We’ll start with the big reason: It's a major hangout for birds. This insanely productive wetlands complex is used significantly by our winged friends for resting and foraging for food.

“Because it's such a large delta, and we have so much eelgrass here, and several other different species, and things like the hooligan and large rounds of very small forage fish, that makes it even more important for migrating birds—which is how it got its status as an Important Bird Area,” says Brenda Wright, a retired fish biologist with the U.S. Forest Service’s Juneau Forestry Sciences Lab and a member of the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge Citizen Advisory Board. She’s also been on the Juneau Audubon Society board since 2000 (and you may remember her as an organizer of the Space and Bird Walk at Juneau’s Twin Lakes).

The bird schedule goes like this (pay attention, bird tourists):

During spring migration, the total number of birds could reach a daily high of more than 16,000 individuals.

From late April 26 through late May, the number of shorebirds passing through is high, especially considering that daily turnover is rapid (shorebirds may spend just one to three days at resting and refueling sites on their way to their worldwide destinations). The southward shorebird migration lasts from late June to early October. Recorded are 41 species of shorebirds, plus one distinctive subspecies (Pribilof Rock Sandpiper). Overall, of the 72 species and subspecies of shorebirds (addressed in the U.S. and Canada National Shorebird Plans), almost half (49%) have experienced apparent population declines since 1970 (a 3 billion bird loss in North America). For 17 of these taxa, all but one of which occurs on the Mendenhall Wetlands, the declines are statistically significant.

The wetlands are also valuable during migrations, primarily April and late August into early November, for a great variety and moderate numbers of raptors, including Short-eared Owls.

The zone is also big for waterfowl with 36 species observed plus two distinctive subspecies: Aleutian Cackling Goose and Eurasian Green-winged Teal. Throughout early spring and early fall, many species of ducks (notably dabbling ducks) and many taxa of geese, favor the area.

Recorded also are 17 species of Larids (gulls, terns, and one jaeger). Species of the greatest number (over 1,000 at one time) have been Canada Goose, Mallard, Surf Scoter, Ruddy Turnstone, Surfbird, Western Sandpiper, Bonaparte's Gull, Short-billed Gull, Glaucous-winged Gull, and American Crow. Substantial numbers (over 500 at one time) of other species include Northern Shoveler, Greater Scaup, White-winged Scoter, Semipalmated Sandpiper, Least Sandpiper, Pectoral Sandpiper, Dunlin, Short-billed Dowitcher, and Common Redpoll.

But these daily high counts only represent a small fraction of the total number of individuals that utilize the Mendenhall Wetlands in any given year.

And this is not even to mention resident birds like Raven and Bald Eagles. Few spins down Egan Drive are absent of the dozens of Bald Eagles perched atop light poles, soaring overhead, or just chilling out on the wetlands at low tides. They're a Juneau thing.

This is all to say the Refuge is a crucial rest area.

“It's one of three major wetland stopping areas in Southeast,” Robus says. “Coming from the south, you come to the Stikine Delta, and then you come to Mendenhall, and then the next stop is Yakutat forelands. And then you're up into Cordova, and on to the breeding grounds.” For context, the distance between the Stikine River Delta IBA and Yakutat Bay IBA is 575 miles as the, ahem, crow flies.

“I'm not radical enough to say that you'd be actually removing the Mendenhall Wetlands from the birds' use but if you harm that use, if you degrade that use, there is no alternative between the Stikine and Yakatat,” he says. “So it would have the effect of making the migration much more difficult. And it's not like birds are doing great as it is.”

Then there’s other wildlife to consider. In addition to birds, birds, birds, there are eight anadromous fish species (fish that spend most of their adult lives at sea but return to freshwater to spawn), and an abundance of marine life according to SEALT and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s fantastic StoryMap on Taashuyee-Chookan.aani/Mendenhall Wetlands. One major river (Woosh eelʼóox̱ʼu héen or Mendenhall River) bisects the area and 14 freshwater streams flow into the wetlands, and all of them support all five species of Pacific salmon and other fish. Robus says ADF&G conducted fish surveys on the wetlands in summer 2023 and added more than a dozen additional streams to the anadromous waters catalog.

“Which means that they're hosting salmon or other anadromous fish and that had never been documented before,” he says. “So there's quite a bit of fish habitat out there and we're finding more all the time.”

He adds that some studies found that fish from the Chilkat Valley area were rearing in the Refuge, which indicates that the Refuge is not just a local haven for wildlife but also has regional value. And then there are Sand Lance spawning areas near the mouth of the Mendenhall River. Those little fish go out and feed bigger fish and whales.

“I like to say that the Mendenhall Wetlands is this wildlife and fish factory that is just churning out biomass and the things that we Alaskans love to have around,” Robus says, “and we don't need to invest anything into it other than not messing it up.”

There are also nearly a dozen different mammals utilizing the Refuge. Robus says the area between Sunny Point and Hendrickson Point is the last undeveloped corridor where mammals—bear, wolf, deer, land otter, and more—can cross between the mainland and Douglas without having to weave their way through a neighborhood.

Finally, there’s recreation, and just plain old scenery—something to consider as Juneau is a major tourist destination.

“The Refuge provides access for subsistence and sport fishing and hunting,” Custer says, “and is a beloved viewshed that defines Juneau in the minds of many residents and more than a million visitors each year.” She adds that the wetlands are important “for thousands of locals who identify Juneau's landscape and public resources with this exceptional open space.”

Robus agrees with the viewshed being essential for tourism. “It is a scenic area that adds to our tourist experience, which is a big thing in Juneau,” he says. Plus, “It is the heaviest hunted waterfowl area in the Southeast region.”

So bird hunting, but also birding—of course.

A major birding site on the wetlands is the Airport Dike Trail. "It's a huge area for people to walk on that airport,” he says. "It's a huge bird-watching area."

He's not wrong. The trail is one of the most-visited birding sites in the Juneau area. The popular year-round path hugs the perimeter of the Juneau International Airport where it meets the wetlands. It’s a stop along the Southeast Alaska Birding Trail, one of 19 sites in Juneau, and it has a hell of a view.

What’s This 40-Year-Old Second Crossing Idea?

We’ve talked a lot about how the Mendenhall Wetlands are important. Now let’s talk about the colloquially known “second crossing”—a plot for a second connection between Juneau and Douglas Island that’s been kicking around since 1984.

Alaska’s capital city is long and narrow, bordering an ice field to the east and the Gastineau Channel, among other waters, to the west. This is considered the mainland. Also part of CBJ is the massive Douglas Island. Aside from boats at high tide and donning waders at low tide, the only connection between this island town/neighborhood with more than 5,500 residents and the rest of Juneau is a single bridge.

The two-lane Douglas Bridge was built in 1980 to replace the original 1935 bridge. “At the time, there was some debate on whether to leave the original bridge standing as a backup to the current bridge and use it primarily for pedestrian traffic, but it was ultimately demolished after construction of the current bridge was complete,” Custer says.

So it may be pretty obvious why a second crossing could be necessary. And many have tried to get it started. Attempts were made around the years 1984, 1992, 1997, 2005, and now.

“Several options have been identified in the past and broad consensus around a single option has not coalesced,” reads an email from the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF). “Funding for large projects is always difficult and requires a sustained public and political will to prioritize this project over other necessary projects.”

But this time around, the funding is a little different.

According to stories from Juneau Empire, KTOO, Alaska Beacon, and other regional news outlets, the money breaks down like this: As of last summer, full funding for the design of a Second Crossing was secured following a $16.5 million grant awarded to the project, which was included in $2.26 billion of U.S. Department of Transportation funding known as a Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grant. That’s in addition to $7 million earmarked for the project from federal funds awarded earlier in 2023. Then CBJ pledged a 5% local match, meaning an additional $866,000 will go to the project from city funds.

“There is a stronger emphasis nationally on the resiliency of the transportation infrastructure,” DOT&PF writes. “The existing bridge is now more than 40 years old and eventually will require repairs/upgrades. Maintaining safe and efficient access to Douglas Island is and will continue to be a priority.”

The money also has to be used for a Second Crossing. “The funding that has been obtained by CBJ (RAISE Grant) for moving the project forward cannot be redirected to other local projects and would go back to the Federal granting agency,” DOT&PF says in an email.

So now, DOT&PF—with CBJ and a team led by engineering consultant company DOWL—have been overseeing the Juneau Douglas North Crossing Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) Study.

According to the website, DOT&PF chose the PEL process to “identify and evaluate the purpose and need for connecting Juneau with Douglas Island.” The PEL process is meant to create opportunities to include public input and advisory committee involvement to conduct an analysis that may be incorporated into a future National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process.

In other words, the PEL study will determine which are the best spots to stick a second crossing between Juneau and Douglas Island for a NEPA review (which then will determine if the proposed actions will have significant environmental effects). What shakes out of this whole thing, theoretically, should be the least environmentally impacted spot where construction can start.

Back to the "purpose and need," the PEL’s findings state that the Douglas Island Bridge accommodates more than 14,000 vehicles per day. Delay is apparent during morning and evening peak periods. When road closures are needed for maintenance, or if there’s an emergency, there are limited access points between Douglas Island and mainland Juneau. What’s more, there’s potential for residential, commercial, industrial, and port development on Douglas Island, which a second crossing could support. Future development in Juneau is constrained by topography and geological conditions, but land on the west side of Douglas Island looks pretty promising for development (like a deepwater port). Overall, the PEL states an improved connection to Douglas Island should address the need for “alternate access and transportation infrastructure resiliency” and “decrease traffic pressure on Douglas Island Bridge and its intersections.”

So we've got 1) congestion, 2) concerns about safety and emergency response, and 3) prospective development on Douglas.

The identified options for a second crossing location, referred to as alternatives, should also strive to meet some additional goals that might perk the ears of some: “Transportation improvements should avoid, minimize, and mitigate impacts to the environment and to residential areas” and “transportation improvements should maintain the visual, cultural, and scenic identity of Juneau and Douglas Island.”

Juneau residents and onlookers know that the PEL study has conducted open houses and listening sessions. Those occurred in 2022 on May 11, September 17, and December 12, and in 2023 on February 3 and May 18. There was a comment and open survey period that ended February 3, 2023, though the PEL states that they are always accepting comments at JDNorthCrossing@dowl.com.

“We have used in-person and online tools to engage with the public. We have an extensive list of technical and regulatory stakeholders that are interested in the project,” writes DOT&PF. “All project advisory committee meetings, attendees, and public comments are available on the project website for public review.”

There are three phases of alternative screenings: pre-screening, Level 1, and Level 2 (which we’re in now).

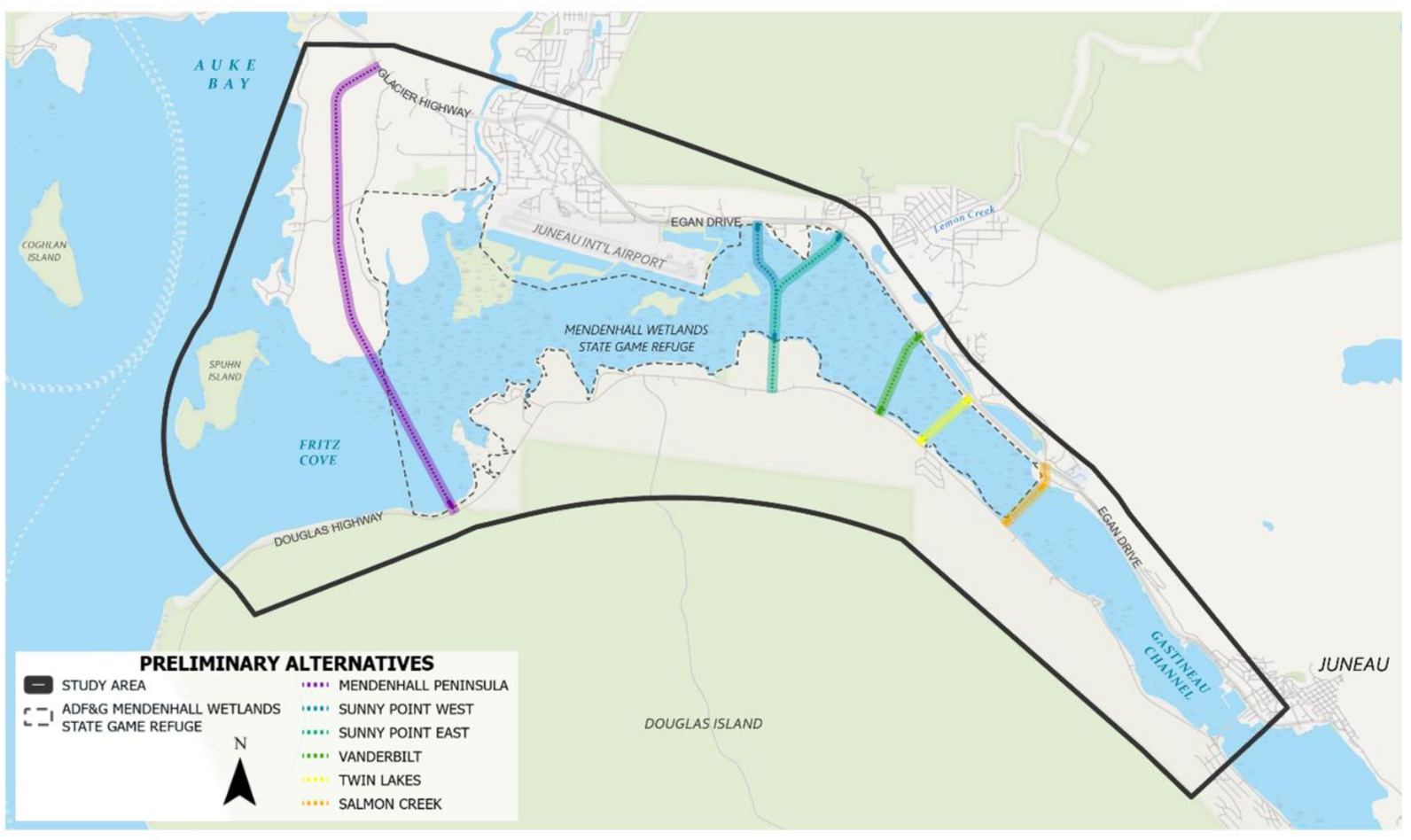

Here’s a StoryMap about the PEL study that outlines the process as it was originally laid out. But to simplify things quite a bit, the process started with multiple alternatives. Alternatives that were “fatally flawed” were eliminated. Then eight alternatives passed the pre-screening process and were considered the Preliminary Alternatives moved into Level 1 Screening. And then we were down to five alternatives: Mendenhall Peninsula, Sunny Point West, Sunny Point East, Vanderbilt, Twin Lakes, and Salmon Creek.

“All the alternatives currently under review ... satisfy the purpose and need to varying degrees,” DOT&PF writes. “A planning-level evaluation of the alternative constructability, impacts, and feasibility is still in progress and will continue through completion of the PEL Study. Selection of a preferred alternative will not occur until the future NEPA document is completed.”

The PEL study was set to conclude in fall 2023 with recommended alternatives for a possible north crossing location. But things went a little off schedule for a while, as large projects tend to do.

As of late February, “The project team is currently receiving feedback from the Advisory Committee members regarding the Level 2 Screening preliminary analysis. Once this feedback is incorporated, the Level 2 Screening will be detailed in a memorandum and posted to the project website,” DOT&PF writes. “The Draft PEL Study and recommendations for the alternative(s) that should be carried forward into the NEPA documentation effort is scheduled for public review in May or June, with the final document scheduled for completion in July 2024.”

Sounds good. Except not all alternatives could go on to the NEPA process. One alternative, the sole off-Refuge option at Salmon Creek, could get eliminated at this next stage.

The Case Made for the Salmon Creek Alternative

Those just-mentioned advisory committees? They are among a collection of what we’ll call pro-Refuge groups. There are the advisory committees—the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge Citizen Advisory Board and the Mendenhall Wetlands Study Group—plus regional conservation organizations, community associations from Sunny Point and Douglas, hunting and fishing groups, birding groups like the Juneau Audubon Society and Audubon Alaska, and other residents.

And there’s a common consensus: They’re not anti-development, not even against a second crossing. Just don’t do it on the Refuge.

Multiple stances have a running theme.

Wright says the stance from the Juneau Audubon Society concerning a second crossing is, “That's a great idea, but nowhere on the Refuge is appropriate.”

Here’s an excerpt from SEALT’s policy statement: “While SEALT welcomes necessary development for the community of Juneau, the Refuge is not a suitable location for any second crossing between Juneau and Douglas Island.”

The Mendenhall Wetlands Study Group, which Robus describes as a confederation of mostly retired professionals from the natural resources fields who have interests, backgrounds, and some level of expertise in the resources of the Mendenhall Wetlands, has a similar statement.

“We don't oppose a second crossing; there are logical reasons for it in terms of development and EMS access and redundancy in case the one existing bridge goes down for some reason,” Robus says. “But where it gets put is a huge question. And my main interest is to keep that route from having serious impacts on the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge.”

So if you’re pro-Refuge but not totally against a second crossing, what’s the solution?

“A second crossing should not be located in the rare and irreplaceable wetlands of the Refuge,” says Custer. “The alternative called ‘Salmon Creek’ is off-Refuge and should be maintained for the NEPA process.”

Salmon Creek is the only off-Refuge option in the five remaining alternatives as of early March. It sits right outside the Refuge’s eastern boundary, just north of downtown Juneau.

The problem is: If the Salmon Creek option is cut during the PEL’s Level 2 Screening, then the four remaining options for the crossing that would make it to the NEPA process, and thus the public comment stage, would be on-Refuge.

This is a major concern for the pro-Refuge people.

Again, Robus: “What we're saying is, we're not against a second crossing. But we believe that the most feasible, low-impact crossing is at Salmon Creek. And that if Salmon Creek is rejected, for good reason, then the alternatives within the Refuge need to be ranked in terms of impact.”

To Robus, a resident of Douglas Island (though he stresses it’s West Juneau, just over the bridge), Salmon Creek also makes sense for those aforementioned goals concerning emergencies. “The Salmon Creek alternative goes straight to the intersection at the [Bartlett Regional Hospital],” he says. “So if you want to improve EMS reach accessibility, Salmon Creek would be a great place to do it because the ambulances could hustle right through that intersection and be at the hospital.”

Robus has more reasons to favor the off-Refuge alternative. Salmon Creek has an existing intersection on Egan Drive, so a crossing could be built without adding a stoplight. It crosses the Gastineau Channel at a constricted, narrow place where there are not a lot of wetlands. He says it would be lower cost in terms of the relatively short distance between the mainland and Douglas.

Salmon Creek also seems the most reasonable to Wright. “Salmon Creek is right at the hospital where you could go from bedrock on our side to bedrock on Douglas,” she says. She points out how it’s far away from the airport, and also stresses that it already has an interchange and stop light.

One reason to worry about the Salmon Creek alternative being cut is only 2 miles from the current bridge. “People say, ‘Why would you want to put it there, it’s only 2 miles,’” Wright says. “Except it's a really good engineering location.”

Another concern among the pro-Refuge folks has been the PEL process itself.

“As a biologist, my real problem is that [the Refuge] has been shown to be a hugely valuable area, biologically,” Robus says. “And that just doesn't seem to be part of the equation as they go through this process.”

Robus says despite the PEL's positive attributes, the downside is many options can be pre-decided so that the NEPA process does not consider the full range of alternatives.

“There are both federal and state regulations that require a developer to look at non-conservation area options when looking for routes for a project like this,” he says. “My big beef with this PEL process, as it's been conducted, is that instead of streamlining things to go into the front end of a NEPA process, which is what it's designed to do, it's having the effect of eliminating all of the non-Refuge alternatives.”

What Could Development on the Refuge Do?

OK, say Salmon Creek gets cut, and we’re left with four on-Refuge alternatives and possibly an on-Refuge crossing. What’s the big deal?

A major development project taking place on the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge, not to mention the resulting structure, wouldn’t be great for the ecological health of the wetlands. It may permanently affect birds and wildlife, and spell trouble for Juneau tourism, in multiple ways. Custer can list some off.

“A second bridge that bisects Taashuyee, the Mendenhall Wetlands, would cause irreparable damage to the habitat available for migratory and resident birds; significantly reduce the supply of nutrients for birds, mammals, and salmon whose populations depend on this area; eliminate accessible waterfowl hunting for many locals; change how boats are able to transit the channel; constrain the Juneau International Airport which benefits from the clear airspace above the Refuge; shrink the wetlands available for safe recreation and gathering of wild foods; and eliminate one of the few areas in Southeast that is wide open scenic space,” she says.

To zero in on migratory birds, they may skip the Mendenhall Wetlands—again, a major stepping stone for birds on their way north and south—if the Refuge were materially degraded.

“I'm not saying that the highway is going to kill all those birds,” Robus says, “But a highway in the wrong spot could really negatively affect the number of birds that get all the way up to the breeding grounds and then all the way back down to their wintering grounds.”

Plus, the Refuge supports birds in unexpected ways. Wright has been overseeing the Tree Swallow Nest Project—an endeavor under the wing of the Juneau Audubon Society—since 2015. A second crossing at say Sunny Point or Vanderbilt would kill that project. “They don't like a lot of traffic,” she says.

Then, an on-Refuge second crossing could wreak all sorts of havoc for birds after construction. It’d push Canada Goose and other birds closer to the airport, which increases the risk of bird strikes with aircraft. There’s also bird strike against the structure itself. A crossing will probably have light fixtures, increasing light pollution. And there’ll probably be a pedestrian or bike path, which could possibly increase human disturbance.

Finally, there’s the big one we touched on earlier: tourism.

Anyone in Juneau can tell you people come to Southeast Alaska from all over the world, and many come to bird. The study "Small sight-Big might: Economic impact of bird tourism shows opportunities for rural communities and biodiversity conservation" found that nearly 300,000 birdwatchers visited Alaska in 2016 and spent $378 million, supporting approximately 4,000 jobs. The study praised Southeast Alaska especially, stating that "the Rainforest region received the most birders and had the largest spending with $184.2 million, almost half of the statewide total.” So you mess with the Refuge—a major stopover for birds and a globally recognized Important Bird Area—you may in turn (and that includes Arctic Tern) be messing with tourism. Just sayin'.

And whales.

“There are baitfish like Sand Lance that spawn and rear in the wetlands that support the humpback whale populations that form the basis for a huge amount of our tourist industry in Juneau,” says Robus.

The Refuge also contributes heavily to the Alaskan scenery for tourists heading out to the Mendenhall Glacier. It sets the vibe for visitors traveling Egan Drive or Douglas Highway. But its ever-present yet subtle beauty can be taken for granted.

“It's not just a big feature by itself, and that's one of its problems,” Robus says. “All of that ecological value and seasonal migratory bird value doesn't leap up and shout at you. It just looks like a swamp.”

He says there’s a general lack of understanding about the cause and effect of development in the wrong place in the wrong way, and how it can diminish Alaska as a product for tourists. Little by little, development projects become "death by 1,000 cuts.”

Also, the Refuge Has Enough Problems

Development on the Refuge is a huge concern because it’s not the only threat to the Mendenhall Wetlands.

First of all, “we've already built an expressway through it in order to commute from the Valley to downtown,” Robus reminds us. Egan Drive was constructed in the 1970s, and it cuts through the eastern edge of the Mendenhall Wetlands (creating what‘s now known as Twin Lakes). The expressway is actually why the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge was established in 1976. And we won’t even get into the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dumping dredged materials in the wetlands in the 1950s, or the Juneau International Airport’s expansion since the 1930s. Robus says human activity has affected or removed around 40% of what used to be the Mendenhall Wetlands.

Next, we’re kind of out of Refuge-level land.

“There are no more mitigation lands that are of the same major as what the Refuge has,” Robus says. Mitigation is the act of offsetting the adverse impacts of development, meaning if construction destroys part of a wetlands network, that could be mitigated, or made up for, by acquiring, creating, or protecting other wetlands.

“But there's no more land like what is in the Mendenhall refuge for birds to use or for fish to use in the same functional ways,” he says. “It would be nice to get some money to fix up some fish habitat on the side of the hill somewhere, but that's not going to prevent the damage to the bird populations that use the Mendenhall refuge.”

Finally, there’s isostatic rebound, otherwise known as glacial rebound or simply "uplift.” This phenomenon of retreating glaciers has been shrinking the official perimeters of the Refuge as its boundary is defined as the extreme high tide line. The good news is that over the last 25 years, “SEALT has conserved 22 parcels around the Refuge in partnership with private landowners and ADF&G and established a permanent upland boundary for the protected habitats of the Refuge,” Custer says.

However, Juneau’s wetlands management policies are based on maps from 1979, meaning the materials used in decision-making do not depict the Refuge’s real boundaries.

SEALT to the rescue again. Along with partners like ADF&G, Territorial Sportsmen, Inc., Discovery Southeast, Adamus Resource Assessment, Bosworth Botanical Consulting, and Audubon Alaska, SEALT is now near completion of the Mendenhall Wetlands Habitat Mapping Project.

“We went out in September [2023] and marched around the Refuge for two weeks in all sorts of weather and did a complete update of the 40-year-old wetland map that was used as the basis for the Refuge in the first place,” Robus says. It’s currently in draft form but they hope to soon deliver to the public a “new wetland map that shows where resource values are today.” And—as Robus says in a KTOO story about the project—the “new maps will better capture what’s at stake if the second crossing moves forward.”

All in all, thanks to declining bird populations, shrinking boundaries, other development projects, and more, the Mendenhall Wetlands State Game Refuge has enough to deal with.

Can we not add a bridge to the mix?

What’s Next?

That’s the 40-year history of Juneau’s proposed second crossing. Though much has happened—or not happened—over the decades, some pretty major stuff is on the docket for 2024.

This means we’ll soon know if the Salmon Creek option will be cut from the recommendations for the alternatives carried forward to the NEPA round. If that happens, the pro-Refuge folks have some work to do.