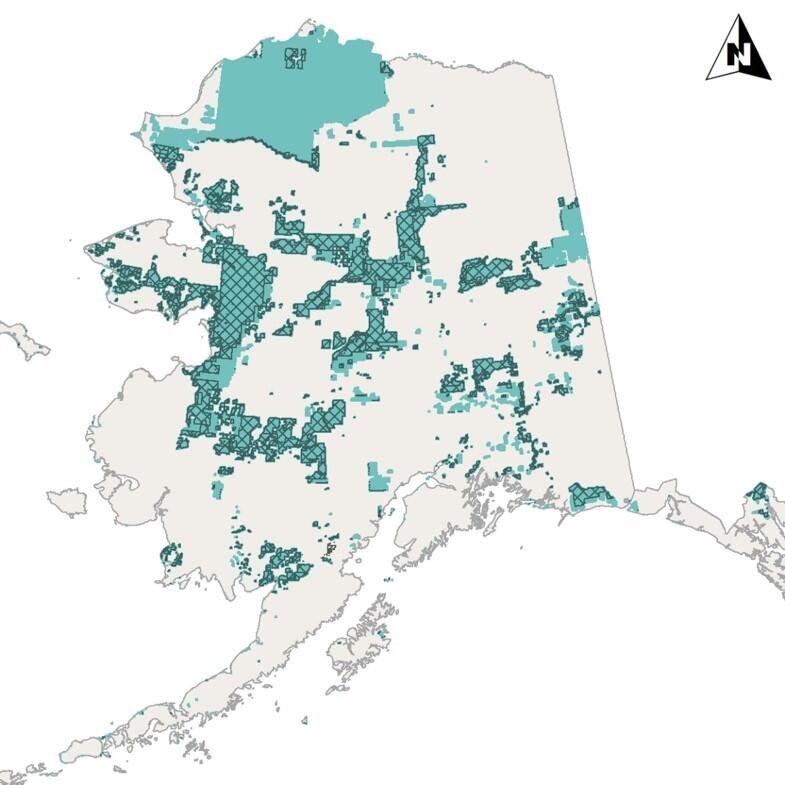

Alaska is known for its public land policy that exists only within its borders (take Special Areas as an example). And “D-1” lands—about 50 million acres of federally managed public lands found in pockets across the state from Bristol Bay to the Brooks Range, Copper River watershed, and northern Southeast Alaska—are no exception.

These spaces, overseen by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), were withdrawn from mineral entry under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971. In other words, when Congress enacted ANCSA, it withdrew under Sec. 17(d) (1) (hence D-1 lands) all unreserved lands in Alaska to allow the Secretary of the Interior at the time to determine whether those lands should remain withdrawn to protect the public interest. Today, D-1 protections cover the majority of each BLM regional planning area, meaning, they are still off-limits to extractive development.

There are many reasons why D-1 protections are important.

This being Alaska, these lands are home to muskox, Dall sheep, all five species of Pacific salmon, brown bears, caribou, and more. We’re also talking countless migratory birds and iconic Alaska species like the Bald Eagle and Spectacled Eider. D-1 lands also play an important role in bird and caribou migration as large tracts of public land provide essential habitat corridors along migration routes.

D-1 lands are also natural climate solutions. Plus, they are the traditional, and essential, hunting and fishing grounds for more than 100 Alaska Native communities.

We’ll go into more detail, but first, let’s talk about why and how 28 million acres of D-1 lands are in jeopardy right now, and what the public can do to keep Alaska’s public lands intact.

D-1 Protections May Go Away for 28 Million Acres

The rub is, despite protections, there are regular attempts to open these areas for industrial development—have been for decades.

Even in 2024, we are still being affected by a final-days decision from the Trump administration that threatens to repurpose 28 million acres of BLM-managed lands for extractive industrial development. The Trump administration previously prepared, but never finalized, five Public Land Orders to lift the D-1 protections for specific lands within Bristol Bay, Bering Sea Western Interior, East Alaska, Kobuk Seward, and the Ring of Fire regions of Alaska.

But the Biden administration is now undertaking an environmental review to better understand how lifting the D-1 protections could affect fish and wildlife habitat, subsistence opportunities, and Alaska communities. On August 16, 2022, the BLM initiated a process to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Then on December 15, 2023, the BLM opened a 60-day comment period seeking input from the public on this rollback. This public process allows Alaskans and conservation allies to add their voice in support of these public lands.

“The draft analysis takes another look at impacts of revoking or maintaining withdrawals across a vast area of BLM-managed lands in Alaska,” said BLM Alaska State Director Steve Cohn in a press release. “We are grateful for the work of many—BLM staff, Alaska Native Tribes and Corporations, and others—who got us to this point. We look forward to engaging with the public over the coming months to ensure we provide a comprehensive analysis to the Secretary to inform her decision on these withdrawals.”

The deadline to comment is February 14, 2024.

This is the first time the BLM is considering how its decisions could affect large tracts of land, critical habitat, and cultural and subsistence resources beyond the boundaries of the usual resource management plans. BLM’s environmental review is not constrained by the rules of the resource management planning process or the limited tools available to protect critical areas. So since the D-1 protections are already in place, this public process is an opportunity to maximize the extent and durability of those protections by creating the justification to keep the protections in place.

Because once these lands are prioritized for development they cannot be redesignated for fish and game conservation, under Alaska’s unique land use system.

"Alaska's BLM D-1 lands represent some of the largest remaining intact landscapes left in the Nation. These lands provide incredible habitat for fish, wildlife, and birds and offer food security for Alaska Native people and communities in the remote reaches of Alaska,” says Emily Anderson, Alaska Program Director at the Wild Salmon Center. “During the comment period, we have the opportunity to speak up for Alaska's public lands and let the Biden administration know that we want these lands protected now and for future generations."

And just like with Ambler Road, we want the BLM to choose the “No Action” alternative and keep these 28 million acres intact.

D-1 Lands and Biodiversity

Alaska’s BLM lands harbor some of the largest intact landscapes left in the country. Large tracts of public land—tens of million acres from Bristol Bay to the Yukon-Kuskokwim region to the northern zone of Southeast Alaska—provide essential habitat corridors along migration routes and natural climate refugia for all five species of Pacific salmon, three of North America’s largest caribou herds, and abundant moose populations.

And of course, these intact areas are crucial for migratory birds and other beloved Alaska species. Think Bald Eagle and Willow Ptarmigan as well as multiple species found on the Alaska WatchList’s Red List. Those include the Red-necked Grebe, Greater Scaup, Spectacled Eider, Black Scoter, Lesser Yellowlegs, Pectoral Sandpiper, Dunlin, Black-legged Kittiwake, Aleutian Tern, and Bank Swallow.

And again, if D-1 protections are removed from these areas, they cannot be redesignated for fish and game conservation.

D-1 Lands and Climate Change

These undeveloped Alaskan lands are also at the forefront of climate change and experiencing real-time impacts that are affecting these animals’ populations and migration patterns.

But these 28 million acres of D-1 lands represent a massive carbon sink. The countless carbon-storing peat bogs, estuaries, and muskeg found across this acreage are all essential for climate change mitigation as they provide natural climate solutions in the form of green and blue carbon storage. And again, with Alaska law, once the protections in place are lifted, they are gone for good.

And finally, not to be dramatic, but this current comment period presents a once-in-a-generation, high-impact opportunity to prioritize the United States’ commitment to fighting climate change and to meeting our national and international commitments to biodiversity. By securing durable protections on millions of acres of Alaska’s BLM lands, the Biden administration can advance its 30x30 land protection goals.

D-Lands and Subsistence

Alaska’s rural Tribal communities are experiencing climate change at an accelerated rate, far exceeding that of frontline communities in the contiguous United States. Protecting Alaska’s BLM lands will help buffer critical resources against rapidly changing conditions so that communities can continue to practice a subsistence way of life in the face of change.

Because working to safeguard the subsistence resources that support Alaska Native communities is also crucial to this. About 80% of the food that sustains Alaska Native communities living off the road system comes directly from surrounding lands and waters. That means BLM’s land management planning decision would impact 75% of all federally recognized Tribes in Alaska. BLM-managed lands support important subsistence resources and serve as the breadbasket for thousands of Athabaskan, Aleut, Denáina, Inupiat, Yup’ik, and Tlingit peoples.

By prioritizing climate-vulnerable and historically marginalized communities, these protections would meet many of the nation’s environmental justice goals. What’s more, when public lands are well-managed and kept healthy, people benefit mentally, physically, and culturally.

Why the Fight is Fought

Along with Tribal leaders, rural villages, regional recreation businesses, and other conservation organizations, Audubon Alaska has had a long history of protecting these important spaces from the impacts of mining and oil and gas development that threaten communities and wildlife.

“Since our office opened in 1977, we’ve been working to safeguard the ecological integrity of Alaska’s landscapes,” says David Krause Interim Executive Director of Audubon Alaska. “Ensuring that D-1 lands are managed for conservation, climate, and subsistence resources is a continuation of this important work.”

Allowing wide-scale mineral and oil and gas exploration and development on these lands represents a major privatization of an important swath of public lands in Alaska. This open

terrain is owned by the American people and should be managed for the public’s benefit. Again, once these lands are prioritized for development they cannot go back to being protected habitat. That’s why this is such an important opportunity to protect public access in Alaska.

Update

On August 27, 2024, the Department of Interior finalized protections for those 28 million acres of D-1 lands across Alaska.

“These places represent some of the nation’s largest remaining intact ecosystems, from high alpine tundra to the pristine estuaries and wetlands in places like Bristol Bay, home to the world’s most abundant wild sockeye salmon runs,” said Emily Anderson, Alaska Director at the Wild Salmon Center, in a press release. “With today’s announcement, the Secretary of Interior and the Bureau of Land Management are demonstrating their commitment to maintaining our nation’s biodiversity, climate refugia, and to listening to the communities most impacted by this decision.”

“This decision is welcome news for Alaska’s birds and communities. D-1 lands are critical to the ecological integrity of the region’s landscapes and irreplaceable values,” says David Krause, the now Vice President for the Alaska program of the National Audubon Society. “Retaining D-1 protections will help ensure healthy habitats, climate adaptation, and resilient populations of migratory birds, salmon, and caribou.”