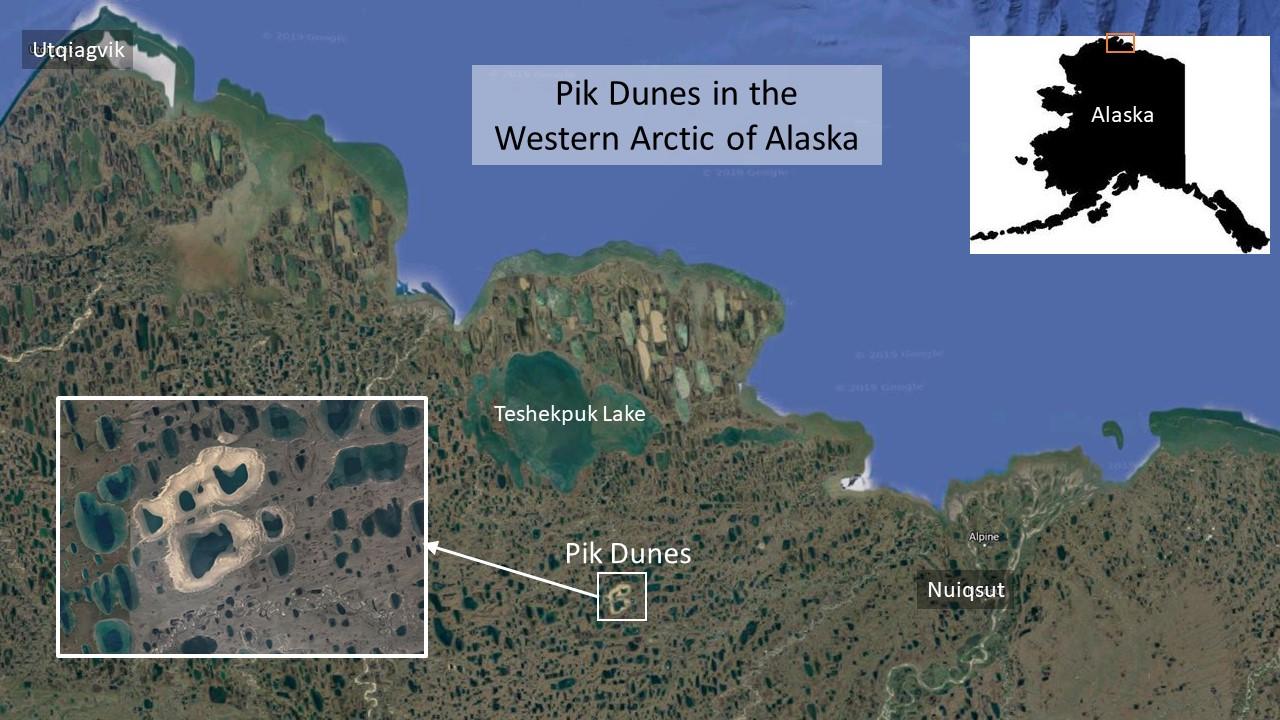

The Pik Sand Dunes is a curious land formation found about 15 miles south of Teshekpuk Lake in the western Arctic of Alaska, within the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A). This strange complex of sand dunes and lakes holds some mysteries that scientists have not yet unlocked. At about 7,000 acres, the Pik Sand Dunes area stands out on satellite photos. The light sand dunes that encircle the basins of several lakes are an unlikely tropical resort in the middle of the Arctic. Beyond their sheer strangeness, the Pik Dunes also harbor unusual plant communities and provide habitat for birds and caribou. Accordingly, the Pik Dunes has long been recognized as an important place worthy of protection in past land management plans.

The rare visitors to the Pik Dunes are astonished by the contrast between the dunes and the surrounding tundra. “What you immediately notice from the air is how different the Pik Dunes are from the surrounding tundra landscape,” says Stan Senner, Vice President of Bird Conservation for the National Audubon Society. “You would think you are somewhere other than the Arctic. The pale sands and incredibly clear blue waters almost make you want to go for a swim.” Senner visited Pik Dunes in 2007, as part of a visit to the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area.

How and when the Pik Dunes formed remains something of a mystery. There are countless small lakes in this part of the Arctic, but the Pik Dunes area is the only place where big extensive sandy dunes surround the lakes. The sand is a soil type that dates to the glacial Pleistocene era. In the past, the sand dunes were actually underwater, forming the submerged sandy bottom and sides of a bigger Arctic lake. The water level in the original lake was drastically lowered as a result of a catastrophic draining event long ago; exactly how long ago, scientists are still trying to figure out. According to scientists at the University of Alaska Fairbanks,[1] there is a large delta fan of sediment just north of Pik Dunes. This washed-out sediment is still seen today as modern day evidence of the big drainage event. Those scientists are now trying to use carbon dating to figure out when that major event may have happened.

Another piece of the Pik Dunes mystery is why the sand dunes have persisted over the millenia and not been slowly covered by tundra vegetation. When the higher water level drained suddenly so long ago, there were smaller lakes left behind in the remaining basins, which are still around today. But the surrounding tundra vegetation did not really creep forward to grow on the newly exposed sand. Even the vegetation that does surround the sand dunes today is a very thin layer of plants, making the area highly sensitive to disturbance. No one really knows why the tundra plants haven’t revegetated the sandy dunes. The UAF scientists are now studying the extent of exposed sand in the Pik Dunes area and comparing the current margins with old photos of the area, to try to understand how vegetation may have encroached on the dunes, which may help explain why the dunes persist today.

Arctic wildlife are not too concerned about the strangeness of the dunes, and some are even attracted to this particular habitat type. Yellow-billed Loons can be seen floating on the lakes, lake trout swim beneath the surface, bird tracks step across the sand, and caribou hang out in the dune habitat. Caribou in the Arctic need access to good foraging areas with tasty tundra plants, but they are constantly plagued by insects like mosquitoes and warble flies, which cause intense irritation. Caribou therefore seek out areas that are relatively free of insects, like sand dunes, barren ridges, and the sandy beaches encircling partly drained lakes. The technical term for these types of places is “insect-relief habitat,” and the Pik Dunes provide just such habitat for the Teshekpuk Caribou Herd. The Pik Dunes also lie within high-use winter and summer calving habitat for these caribou.

Some interesting plant communities also grow in the margins of the sand around Pik Dunes. The plant genus Eritrichium is made up of a group of pretty, blue, alpine forget-me-not flowers. Until recently, the particular Etrichium species found growing in the northwest Arctic was thought to be the same as a widespread species that spans Arctic Alaska. But in 2017, scientists found that the Eritrichium around Teshekpuk is a unique species that only grows around Teshekpuk, including near Pik Dunes and the Meade River.

The Pik Sand Dunes are enigmatic, interesting, and important. They are currently protected from oil and gas development and infrastructure by virtue of their location within the section of the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area that is unavailable to oil and gas leasing. Along with the other fascinating and unparalleled aspects of the Teshekpuk region in the Western Arctic, the Pik Dunes merit ongoing protection.

Sources:

Bureau of Land Management, 2012, Final Integrated Activity Plan/Environmental Impact Statement.

Alaska Center for Conservation Science, University of Alaska Anchorage, 2018, Condition of lakes in the Arctic Coastal Plain of Alaska: water quality, physical habitat, and biological communities (A report prepared for the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation), available at https://dec.alaska.gov/media/14433/adec-npr-a-lakes-2013-final.pdf

Benjamin M. Jones, Christopher D. Arp, Matthew S. Whitman, Debora Nigro, Ingmar Nitze, John Beaver, Anne Gadeke, Callie Zuck, Anna Liljedahl, Ronald Daanen, Eric Torvinen, Stacey Fritz, Guido Grosse, 2017, A lake-centric geospatial database to guide research and inform management decisions in an Arctic watershed in northern Alaska experiencing climate and land-use changes, Ambio 46(7):769-786, doi: 10.1007/s13280-017-0915-9, available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13280-017-0915-9.

David F. Murray, 2017, Notes on Eritrichium (Boranginaceae) in North America III. Three new species of Eritrichium, Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 11(1): 19-23, available at http://legacy.brit.org/webfm_send/1756

Ingmar Nitze, Guido Grosse, Benjamin M. Jones, Christopher D. Arp, Mathias Ulrich, Alexander Federov, and Alexandra Veremeeva, 2017, Landsat-Based Trend Analysis of Lake Dynamics across Northern Permafrost Regions, Remote Sensing 9(7):640, doi:10.3390/rs9070640, available at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/9/7/640.

[1] Benjamin M. Jones, personal communication, April 5, 2019; these scientists are funded by a new grant from the National Science Foundation focused on rapid lake drainage in the Arctic.