There are few places as off-the-charts important for birds as Izembek National Wildlife Refuge (Izembek). Izembek lies along the Bering Sea side of the Alaska Peninsula and is a stopover site for multitudes of birds migrating to and from Arctic breeding grounds. In sum, it’s one of the most critical migratory bird staging and wintering habitats in the world.

But there’s long been talk of a road that, despite being less than 20 miles, would sacrifice key habitats and bring about significant long-term degradation of bird and wilderness values. The issue dates back to the 1980s, but as of November 13, 2024, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) under the Department of the Interior released a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (draft SEIS) that recommends a multi-part land exchange and road as a preferred alternative.

Not an expert on this particular issue? Here is some background, and how to take action.

What Is Izembek and How Is it Important to Birds?

Izembek was established as “a refuge, breeding ground, and management area for all forms of wildlife” in 1960. In 1972, Izembek Lagoon was protected through the Alaska Submerged Lands Act and became the Izembek State Game Refuge. In 1980, a majority of its acreage was designated as Wilderness (making the area off-limits to vehicles, roads, and more) under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). In 1986, Izembek Lagoon was one of the nation's first sites to be named a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands.

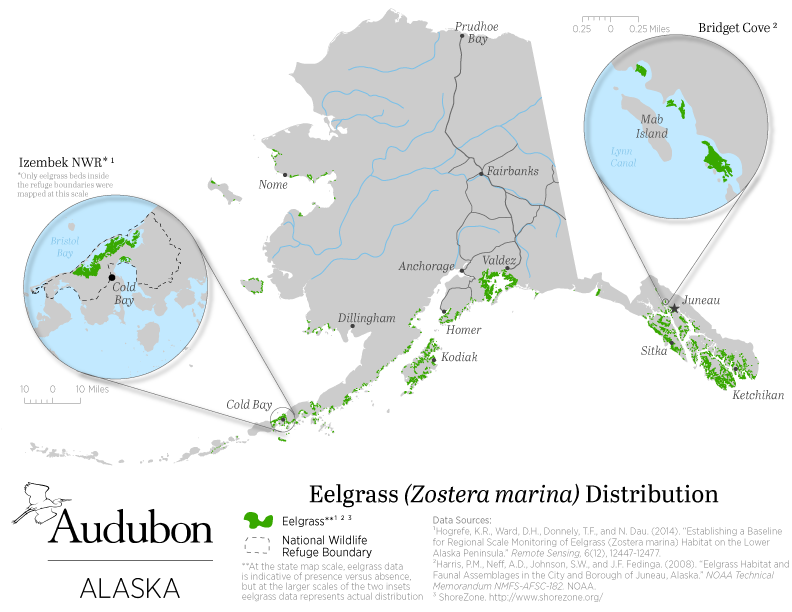

The area is also formally known as the Izembek-Moffet-Kinzarof Lagoons Important Bird Area (IBA)—an IBA of global significance designated by BirdLife International and National Audubon Society. The presence of large eelgrass beds (a type of aquatic marine vegetation) makes this site one of the most important migratory bird staging and wintering habitats in the world. Izembek regularly supports more than 90% of Brant that use the Pacific Flyway. Essentially the entire Pacific Brant population stops in Izembek to refuel. What’s more, in today’s warmer climate, about 30% of the Brant are remaining at Izembek for the winter, with an increasing trend over time, making Izembek ever more important for this species.

Izembek also supports more than half the world population of Emperor Geese and a significant percentage of the world population of Steller's Eider and Taverner's Cackling Goose. There are also Tundra Swans, ptarmigan, and Bald Eagles. And Izembek’s cold-water lagoons and internationally significant wetlands are critically important resting places for migrating waterfowl. Overall, more than 82 bird species have been documented here as well as mammals like caribou, brown bears, wolves, and wolverines.

So the land is important to the birds, but why are the birds important to the people?

“The reason is simple: Migratory birds connect us,” writes Edgar Tall Sr., Chief of the Tribal Council for the Native Village of Hooper Bay, in an Anchorage Daily News opinion piece. “And we rely on these birds, especially Pacific black brant and emperor geese, for our health and continued existence.”

Chief Tall says Brant and Emperor Geese are hunted in spring until they start laying eggs, then again in the fall. “Harvesting these birds helps us recover from our long winters. Then, at the end of our brief summer, they help us prepare again for the long winter.” Chief Tall writes that food insecurity caused by climate change, industrialization, hunting restrictions, and the salmon crisis is changing how Alaska Native communities like his traditionally hunt, fish, and gather. Traditional foods like Brant and Emperor Geese, plus moose and fish, make up more than half of what he and his community eat.

“With all the changes and disruptions to our natural world, we now must travel farther to find our traditional foods,” Chief Tall writes. “This is more dangerous and forces us to make hard choices about whether to bring young hunters along to teach them our traditional ways of life.”

What’s the Problem With a Road Going Here?

Izembek comprises a narrow isthmus and its two surrounding lagoons, Izembek and Kinzarof (hence Izembek-Moffet-Kinzarof Lagoons IBA). The proposed road would be 18.9 miles long through this area, connecting the communities of King Cove and Cold Bay. It would give King Cove residents road access to Cold Bay’s all-weather airport and therefore medical care. Currently, King Cove residents have to travel across the bay by plane or boat to access Cold Bay, which can be a dangerous journey thanks to frequent inclement weather.

But 20 resolutions from 78 Tribes and one village corporation have been submitted to the Interior Department in opposition to a potential road and/or land exchange in Izembek. The Arctic Village Council, Venetie Tribal Council, Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government from Gwich’in Athabascan Lands in the Brooks Range, and the Native Village of Tyonek from the Upper Cook Inlet, among others, were requesting that the Department of the Interior not release the draft SEIS until all of the concerned Tribes can consult with top decision-makers. But again, the draft SEIS was released in mid-November.

Climate change plays into this, too. As mentioned, Izembek is home to one of the world’s largest eelgrass beds, which is also an important climate change mitigation and adaptation tool. Eelgrass is a remarkably effective buffer against one of the most catastrophic climate change impacts: ocean acidification. This occurs when atmospheric carbon dioxide is absorbed by the ocean, lowering the water’s pH. Recent studies have shown that eelgrass provides a powerful buffer against this phenomenon. The Bering Sea is particularly sensitive to ocean acidification and already experiences disproportionally high acidification.

Eelgrass has been found to annually sequester carbon at a rate 10 times greater than mature tropical forests, and stores three to five times more carbon per equivalent area than tropical forests. That makes Izembek’s massive eelgrass lagoon, one of the largest of its kind, an important carbon sink. When these habitats are damaged or destroyed, it is not only their carbon sequestration capacity that is lost. Carbon stored in the habitats can also be released, contributing to increased levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. And seagrasses have declined by 30% globally in the past 150 years, and that includes eelgrass.

A little more than 305 million acres of land in the U.S. are currently protected and of that, almost 145 million acres of protected land are in Alaska. Virtually all of those lands are governed by ANILCA. So road construction here undermines the protection of almost all of the 145 million acres of protected lands in Alaska. USFWS has consistently found that a road across the narrow isthmus between Izembek and Kinzarof lagoons would be incompatible with the purposes for which Congress created Izembek in the first place, which is to conserve fish and wildlife populations and their habitats to fulfill the nation’s international treaty obligations (such as the four migratory bird treaties and the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance), to provide for continued subsistence by residents, and to ensure water quality and quantity within the refuge.

This means road construction here would set a dangerous precedent, endangering refuges and Wilderness areas across the nation, and undermining multiple bedrock environmental and conservation laws including the Wilderness Act, National Environmental Policy Act, National Wildlife Refuge Improvement Act, and ANILCA.

What Are the Alternatives?

In the draft SEIS, alternatives 4 and 5 offer marine transportation options—"Hovercraft from Northeast Terminal" and a "Lendard Harbor Ferry with Cold Bay Dock Improvements."

"We understand and respect the concerns of the people of King Cove and others who want safe and reliable transportation connecting King Cove to Cold Bay, but we respectfully disagree that a road is the best solution," writes Chief Tall in a follow-up opinion piece in Anchorage Daily News. "... We will continue, as we always have, to seek a solution to this issue that serves the needs of King Cove without harming others, and we remain ever hopeful that we might still change the hearts and minds of federal decision makers."

Non-road alternatives have been outlined and practiced for years. One alternative has been an interesting installment of the Izembek timeline: a hovercraft. From 2007 to 2010, a top-of-the-line, 100-foot hovercraft called Suna X provided regular ferry and emergency medical service between King Cove and Cold Bay. It successfully performs more than 30 medical evacuations in most all-weather conditions, requiring about 20 minutes to travel from King Cove to Cold Bay. The hovercraft, however, was transferred for use in 2010 to nearby Akutan, which never requested additional funds for continued operation or maintenance out of King Cove. Eventually, the borough chose to suspend hovercraft service, saying it was having staffing and funding problems.

One thing to keep in mind is that in 2023, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration, Cold Bay received a Port Infrastructure Development Program grant for $43,376,746. "This project will include the design, permitting, and construction of a new dock to replace the community’s only existing dock, which is nearing the end of its useful service life," reads the press release. The new dock will be designed and built to accommodate commercial use, freight and fuel transportation, private vessel use, and public uses like emergency medical services and public transportation through the Alaska Marine Highway System."

Pair the $43 million with the fact that in 2015, "a marine ferry alternative was determined to be 99.9% dependable by the Army Corps of Engineers," according to Defenders of Wildlife. That means the Army Corps of Engineers has already determined a marine alternative would better meet the needs of the region and would not undermine the integrity of ANILCA and Izembek.

What Can We Do?

The “Potential Land Exchange for a Road Between King Cove and Cold Bay” public comment period opened on November 15. Public comments will be now accepted until February 13, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (7:59 p.m. Alaska time).

To recap, Izembek—one of the world's most important migratory bird staging and wintering habitats—is under severe threat. A pending land exchange would allow the construction of a 19-mile road through the heart of Izembek, undermining public land laws and putting Wilderness and wetlands at risk of permanent damage. There are better, more reliable alternatives to building this road. Tell the U.S. Department of the Interior to reject the road and support proven, win-win solutions for people and wildlife. Submit your comment by February 13.

Audubon stands behind the 78 Tribes and one village corporation that oppose a potential road or land exchange in Izembek’s Wilderness, and we urge the Secretary and the Department to do the same. Join us by taking action here.