Three months ago, I embarked on the internship assignment of my dreams. Armed with a Nikon D3200, a 2008 birding map, and a healthy supply of coffee, I set out with my coworker to photograph all 34 sites on the Anchorage Birding Trail across the traditional lands of the Dena’ina Athabascan people. In the time since, I’ve explored some of the city’s most diverse and breathtaking habitats, capturing their unique beauty through the lens of my camera.

My assignment afforded me an invaluable and in-depth perspective of Anchorage as an incredibly unique place. I’ve slid down glacial snow, sunk knee deep in mud, and hiked in the northernmost temperate rainforest to observe the birds that shape the region’s vibrant and remarkable ecosystems. Thirty-four sites and more than 2,000 photographs later, I’ve gained a comprehensive understanding of all that the Anchorage Birding Trail has to offer. For birders, great news: Each site is well worth your time, and my eBird has never seen more submissions.

But even for those who are less bird-inclined, the trail has plenty to offer. These locations are also home to fascinating hidden gems that make visiting a rewarding experience. From desert landscapes to abandoned military bases, the Anchorage Birding Trail is full of wonders just waiting to be explored.

A Year-Round Rainforest

While exploring Russian Jack Springs Park, I expected all the usual Anchorage beauty—trickling streams, wildflowers, and wooded forests populated with songbirds. What I didn’t expect was to be transported to the rainforests of Costa Rica or the Sonoran Desert of Arizona.

Situated inconspicuously on a grassy hilltop, the Mann Leiser Memorial Greenhouse is a portal to another world. Stepping through the doorway, I was met with a wave of humidity and warm air. As the rest of my senses caught up, I took in my surroundings—lush, thick vegetation, vines creeping along the greenhouse wall, and air heavy with moisture. Bright orange koi fish swam lazily through an amber-colored pool, and water misters emulated the near-constant condensation of an equatorial paradise. Nestled into a 20-by-20-foot building, a tropical rainforest thrives throughout temperate Alaskan summers and harsh polar nights.

Stepping into the next room, the humidity dissipated, immediately replaced by a desert heat as soon as I stepped over the threshold. Sun streamed in through the translucent roofing, a stark contrast to the thick jungle canopy of the previous ecosystem. The room was a fantastical collection of desert species, plants I had seen in the stark landscapes of Death Valley and the Mojave, but never expected to happen upon in Alaska. Towering cacti, symmetrical succulents, and spear-shaped Giant Agave meshed into a unique desert landscape, one so believable my coworker remarked that she was homesick for Phoenix.

Exiting the greenhouse into a brilliantly blinding summer day, I felt as if I had been let in on a little secret: Rainforests and deserts exist in Alaska—if you know where to look.

It’s A Bird … And A Plane!

Some of Nuch'ishtunt, or Point Woronzof’s, birds look a little different than others. And by “different,” I mean some are feathered, and some are 136,000-pound metallic winged contraptions hurtling through the sky at 180 miles per hour.

At Point Woronzof, a stunning expanse of beach on the tip of West Anchorage, flocks of Short-billed Dowitchers and White-winged Scoters dot the shore. Bank Swallows nest in the high bluffs overlooking the rocky coast. While these wonderful species provide great birdwatching, if you find yourself tiring of peering through binoculars, have no fear—there are plenty of winged spectacles you can spot with the naked eye.

This prime birding area backs up against the Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport, which means that by watching for birds, you’re also inherently watching for airplanes. During take-off and landing, planes soar low overhead, allowing you to snap photos and take in the thunderous rush of a Boeing 737 launching into the air.

Many residents and tourists alike perch atop a small grassy hill near Point Woronzof Park, scouting the planes as they come and go. Originally puzzled by this phenomenon as my flight landed in Anchorage back in June, I’ve since joined the masses, tilting my head to the sky to gaze in awe at the planes, as well as the birds, that make Point Woronzof special.

Fruitful Finds in Arctic Valley

If you’re looking for a lesson in meditation (and tasty snacks), go no further than Arctic Valley Ski Hill. Home to flittering Boreal Chickadees and bulbous Willow Ptarmigans, this ski slope also hosts large populations of wild blueberries and low-bush cranberries in the summer.

Intrigued by the berry pickers dotting the mountainside, my coworker and I set out with makeshift berry buckets: hers was an empty yogurt tub, mine a washed sour cream container. Berry picking, as it turns out, is equal parts meditative and delicious. During the next hour spent scouring the hillside, my sole pursuit became finding clusters of ripe berries ensconced in low-to-the-ground shrubbery. Settling into a rhythm—scan, find, pick, (eat), repeat—I found myself noticing the intricacies of alpine flowers and chirps of Lapland Longspurs.

The fruits—quite literally—of my labor were ¾ of a tub of blueberries and a new favorite hobby. Following some tedious destemming, the blueberries were transformed into a delectable pie. Arctic Valley offers it all: a beautiful spot for bird-watching, a bountiful site for berry-picking, and a peaceful way to connect with nature.

Ship Creek’s Surprising Stream of Life

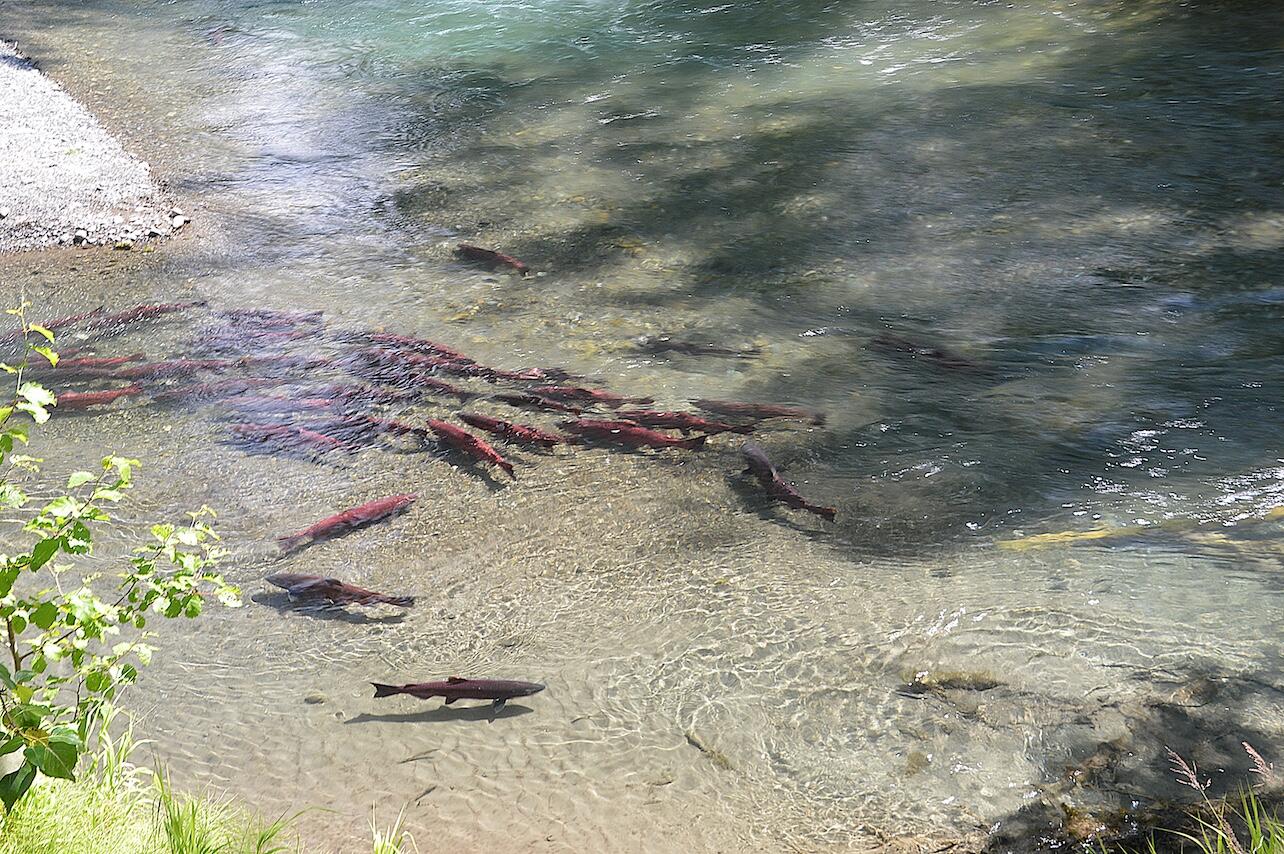

It’s not every day you see wild salmon in the middle of a city. Unless you’re at Ship Creek in the summer, in which case, it is every day. Nestled between a railroad and a busy street, this waterway provides a haven for spawning salmon as they endure their final upstream journey.

Ship Creek is a 10-minute walk from my office, so I’ve had the pleasure of visiting several times throughout the summer. Each visit, I’m met with a new species of salmon. Chinook salmon greeted me upon my early June visit, Coho salmon came through in July, and as I write this, hordes of Pink salmon congregate near the Ship Creek Dam. If you’re looking for a place to catch fish, or even just watch fish, Ship Creek has a plentiful supply all summer long.

In fact, Dgheyaytnu, or the mouth of Ship Creek, hosts a plethora of wildlife. Where the river pans out into mudflats, Canada Geese gather, waddling across the slick floodplain at low tide. Herring, Bonaparte’s, and Mew Gulls inhabit the skies and shores, attracted by the salmon. Biking into the office, I’ve had the luck to see beluga whales bobbing up and down in the water.

If you’re hoping to appreciate Alaskan wildlife within the comfort of an urban setting, Ship Creek is the site for you. I’ve yet to be disappointed by this natural gem nestled into the whirlwind of downtown Anchorage.

Digging Into Crow Creek’s History

Driving along Crow Creek Road, our hunt for Spruce Grouse and Pine Grosbeaks was interrupted by a simple wooden sign advertising the “Crow Creek Gold Mine.” Intrigued by the prospect of a gold mine in the middle of a dense forest, my colleague and I took a detour to investigate. The woods opened up to an idyllic mining village backed by pine trees and snow-capped mountains. A golden retriever eagerly wagged her tail as we approached the steps of the main building.

Rustic buildings and mining equipment fill the grassy field, offering a window into Alaska’s gold rush. Established in 1896, Crow Creek Gold Mine is still operational today, with experienced miners and visitors alike heading to the riverbed to pan for gold. For those who are more interested in a history lesson, the mine offers self-guided tours of the original settlement, complete with mining artifacts of the time. Wildflowers adorn the property, hanging from porches, fenceposts, and an ancient green automobile. Well-preserved, this hidden gem truly brings you back in time.

If you’re interested in a slice of Alaskan history along with your birding, be sure to take the short detour to explore this snapshot of the past.

Don’t Moose Out on Kincaid

My first two weeks in Anchorage were surprisingly moose-less, save for the taxidermy bull moose that greeted me in the airport terminal upon my arrival. I began inquiring about where I might see one, and every local pointed me in the same direction: Kincaid Park.

On my 26-mile bike ride to Kincaid (the farthest I have ever biked in pursuit of anything), I passed through several other birding trail sites, gazing with wonder at Arctic Terns at Westchester Lagoon and Sandhill Cranes at Fish Creek Estuary. By the time I reached my destination, I had experienced breathtaking views of mountains and mudflats, as well as the equally breathtaking experience of biking up a very steep hill. But the effort paid off; I was rewarded with a mother moose and her baby peacefully grazing in the woods along Kincaid.

If you’ve already seen your fair share of moose, Kincaid offers amazing recreational opportunities in addition to wildlife viewing. An 18-hole disc golf course meanders through the park. Over 100 miles of cross-country skiing trails wind through the woodlands. As the snow melts, these trails transform into havens for hikers and mountain bikers. And if you’re more interested in sightseeing, the Kincaid Outdoor Center has a roof deck that provides views of Cook Inlet, Nutuł’iy (Fire Island), and Denali on a clear day.

Salmon Up Close

Before moving to Alaska, a quick Google search yielded photos of snowcapped mountains, moose traipsing through marshlands, and bright red salmon battling their way upstream. I later saw that last scene in real life at the William Jack Hernandez Sport Fish Hatchery.

Despite its fish-centric name, the hatchery is a site on the birding trail. Bordered by Ship Creek, the glacial-blue waters offer prime viewing conditions for Chinook salmon, their red bodies strikingly distinct against the rocky riverbed. Clustered together, the salmon stayed in place as they languidly fought the current, allowing visitors to gather and observe from the platform.

The salmon-filled river was just the beginning. Inside the hatchery building, which doubles as a museum, 6 million fish inhabit the tanks, waiting to be released into streams and lakes throughout the summer and early fall. Rainbow trout and Arctic char swam in dizzying circles as I peered through viewing windows, taking in the massive vats of fish. Documentaries, info panels, and fish-inspired art covered the hallway, creating a lively and educational environment perfect for adults and kids alike.

The interconnectedness between fish and the rest of Alaska’s wildlife is on full display at the hatchery. Common Mergansers and Belted Kingfishers frequent the river, American Dippers nest in the decommissioned fish ladder propped against the dam, and bears sometimes stop by for a salmon snack. While the thrill of spotting that first shockingly red salmon was unforgettable, I found myself equally captivated by all the wildlife sustained by the hatchery’s waters.

“A City Under One Roof”

Once you emerge from the dark, narrow, seemingly never-ending tunnel that functions as the area’s only entrance, Whitter becomes an idyllic seaside town. Mountains appear to emerge from the ocean, carpeted in thick green vegetation and topped with year-round snow. High on the slopes, glaciers glare in the sunlight, their slow ice-melt transforming into raging waterfalls that pour into the ocean. Sailboats rock back and forth in strikingly blue water, gulls and kittiwakes soar overhead, and souvenir shops line the street.

Whittier is picturesque. Except for the Buckner Building.

Nestled farther back into town, the decrepit Buckner Building almost blends into the surrounding forest. But for a horror-movie fanatic like myself, the crumbling facade immediately caught my interest. As I approached the building, its decades of neglect became more apparent. Shattered windowpanes afforded me a view into the structure. Water dripped rhythmically from the ceiling, forming pools that reflected rippling patterns onto the walls. Rusted stairwells led skyward to countless empty rooms covered with moss and graffiti. The building’s apocalyptic exterior felt even more fitting when I learned about its intended purpose.

Completed in 1954, the Buckner Building was designed to be a military base and self-sustaining city, housing over 1,000 soldiers during the Cold War. In the event of a doomsday, the building was equipped with all the amenities of life—a barbershop, a cafeteria, a jail, even a bowling alley. However, the only attack that ever shook Whittier was the 9.2 magnitude Good Friday Earthquake, which the structure dutifully withstood. In 1960, the Army stopped operating in the building, and it has remained dormant ever since.

Despite its disuse, it's not every day you can see an abandoned, very-haunted-looking military base looming over a charming seaside town. If you’re after a one-of-a-kind birding trip—with rare seabirds, towering glaciers, an eerie tunnel, and a deserted Cold War relic—Whittier delivers.

Next Stop for the Anchorage Birding Trail

Reflecting on my past three months as Audubon Alaska's Outreach and Communications Advocate, I’m incredibly grateful to have spent my time photographing and exploring the Anchorage Birding Trail on Dena’ina Ełnena. Each site instilled a sense of wonder and provided me with a deeper understanding of the Anchorage area as a wild, intricate, and flourishing city. Though I was following the birds, I found myself constantly discovering wildlife, natural landscapes, and manmade creations that piqued my curiosity, took my breath away, and served as an important reminder that everywhere we protect birds, we also protect nature, history, and community.

If my summer experience has inspired you to go birding, gold panning, or berry picking, I have some exciting news for you. Coming next year, the Anchorage Birding Trail will be available digitally on Audubon Alaska’s website, complete with photos, up-to-date information, and maps. You’ll have 34 new adventures to explore, just a click away. Enjoy.

—Grace Miller is Audubon Alaska's Outreach and Communications Advocate.