Years ago, land management agencies charged with stewarding public lands, like National Parks, National Forests, and Wilderness areas, came up with ways to measure Wilderness. Wilderness is more a human-derived concept than a state of land, but we did try to define it as part of the 1964 Wilderness Act. It became a legally binding, measurable quantity even amidst turmoil and controversy of trying to quantify something like a untrammeled hike through the Kobuk Valley, or a traditional caribou hunt in the southern foothills of the Brooks Range on the heels of small group of the Western Arctic Caribou Herd.

The four federal agencies managing wilderness - (BLM, FS, FWS, NPS) - worked together to create an operational definition of wilderness qualities linked to the original definition of the 1964 Wilderness Act. These qualities are:

• Untrammeled: Wilderness ecological systems are unhindered and free from intentional actions of modern human control or manipulation.

• Natural: Wilderness ecological systems are substantially free from the effects of modern civilization.

• Undeveloped: Wilderness is essentially without structures or installations, the use of motors, or mechanical transport.

• Solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation: Wilderness provides outstanding opportunities for solitude or primitive and unconfined recreation.

• Other features of value: Wilderness may have unique features of ecological, geological, scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.

Rather than reflect on the history of lands and waters, and address present Indigenous stewardship since time immemorial, the Wilderness Act, and these five qualities, were meant to protect places and ways of life for an uncertain future. At the time the Wilderness Act was written, roads and mechanized equipment were sprawling across public lands seen as commodities for natural resource industries. Wilderness became a place of pause.

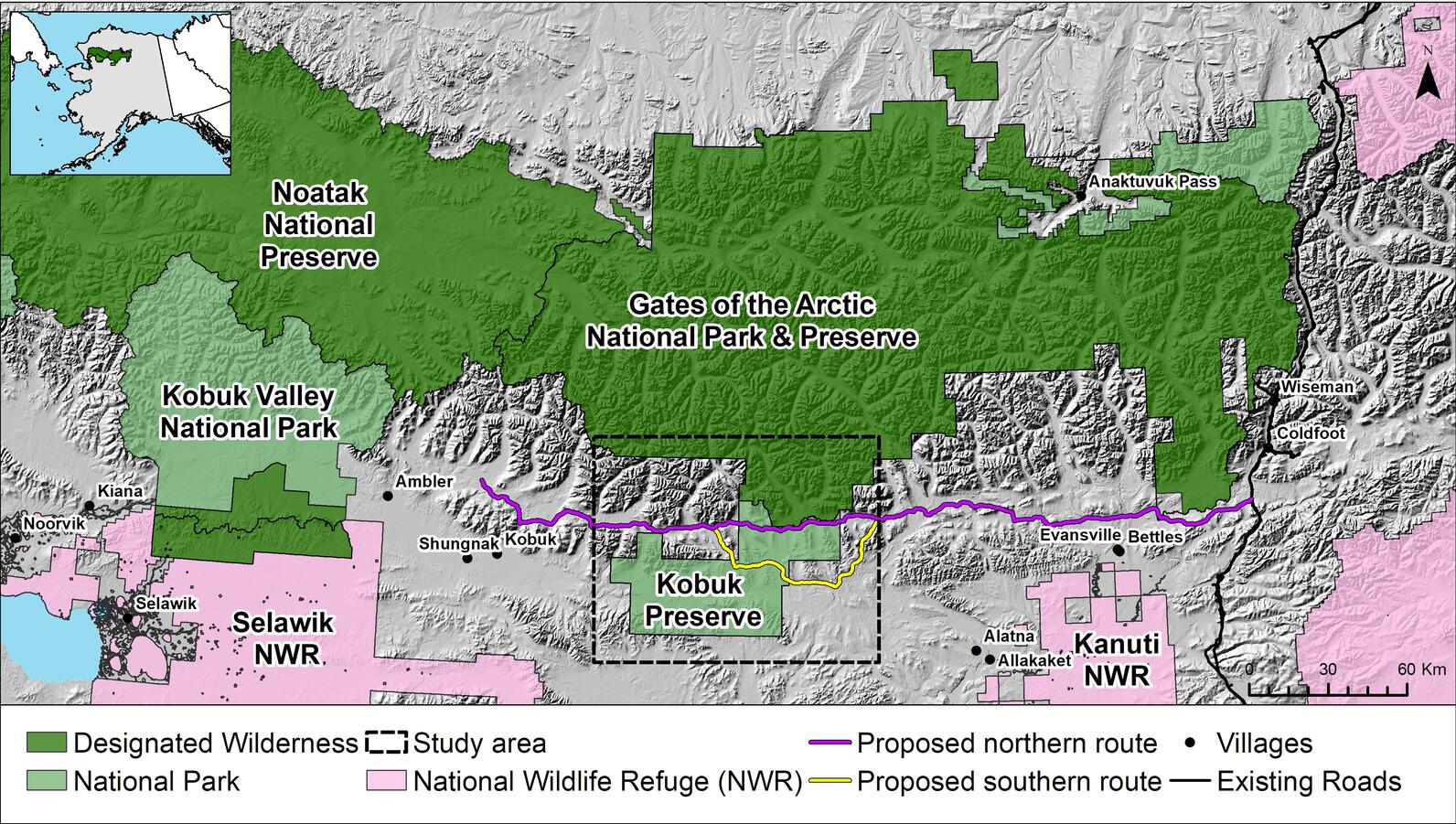

We use this framework of wilderness character to analyze the potential impacts of the Ambler road corridor on wilderness character of national parklands through which the road will slice a section. In our analysis, we show the various ways that wilderness character and quality will be impacted. We wrote this paper, "Evaluating Potential Impacts of Proposed Industrial Access Road Routes on Wilderness Character in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, Alaska," because wilderness is a legislated characteristic of our mutual public lands, and no analysis of impacts to wilderness was included in the original agency review of the potential Ambler Road. Wilderness is one of many, many values that would be impacted by the development of the Ambler Road because the road would open up a currently roadless region of western Alaska on the edge of the largest roadless area on the planet. Though the decisions will come down to values, we should not ignore the potential impacts that will reverberate across the tundra and tussocks.

We encourage you to watch Paving Tundra from filmmaker Jayme Dittmar who travels 350-miles along the proposed Ambler Road corridor into the Brooks Range to ask what would be lost if the tundra is paved, and how the road and mine development would impact the indigenous people and land, in particular the regional fisheries and the 250,000 strong Western Arctic Caribou Herd that migrates through the Gates of the Arctic.

Take action before January 21st to support the people and tribes of the region by submitting your comments here.