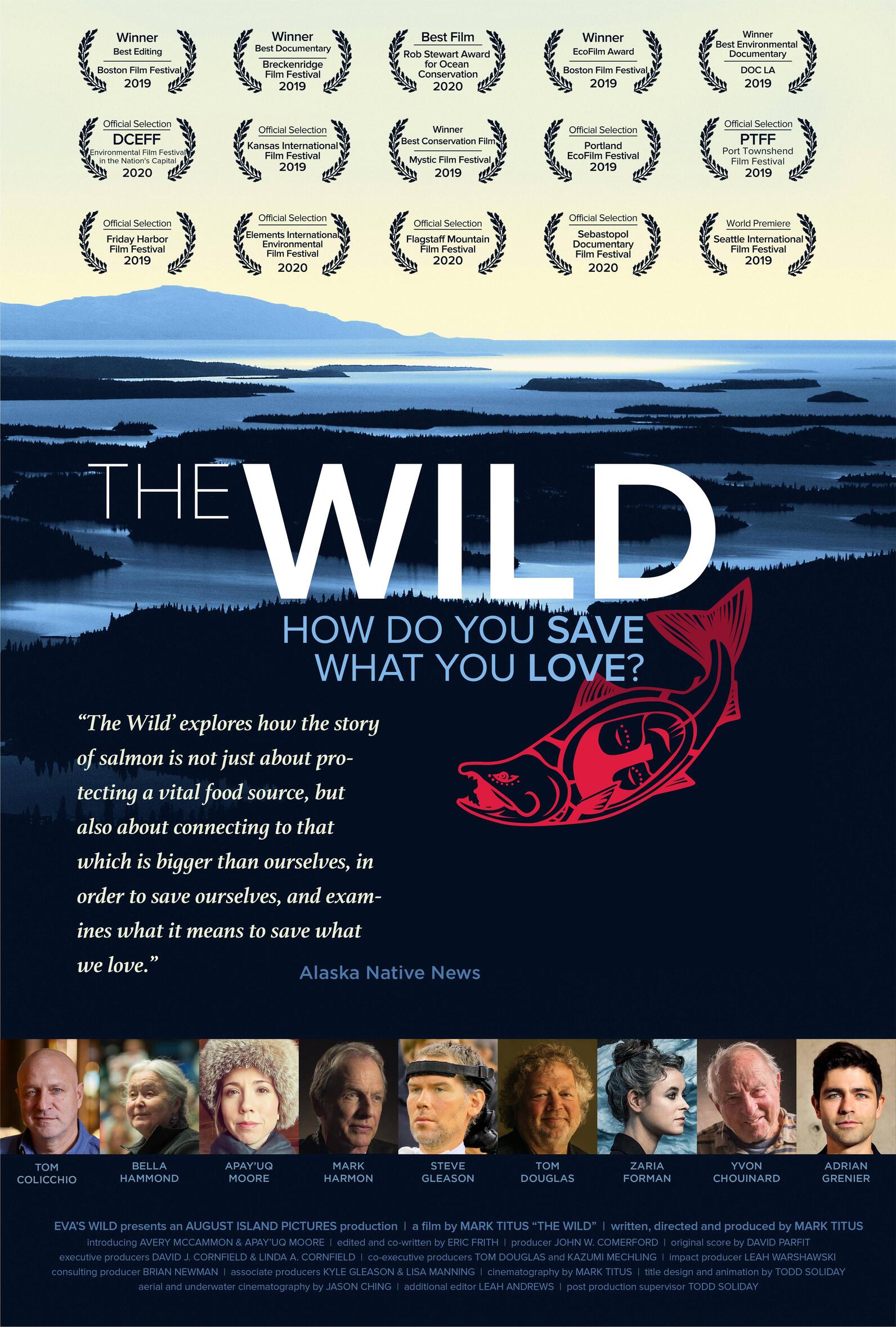

This week, Audubon Alaska encourages you to watch The Wild, an award-winning documentary that tells the story of filmmaker Mark Titus who returns from a personal struggle with addiction to the Alaskan wilderness where the world’s largest sockeye salmon fishery faces devastation if Pebble Mine is constructed. Prepare to be inspired by our interview below with Mark who shares his advocacy work and encourages us all to submit our comments and concerns to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency by September 6, 2022 to veto the harmful Pebble Mine.

Visit Audubon Alaska's Take Action page here to personalize your message to the EPA today in order to help protect vital habitat for countless migratory birds and the world’s greatest concentration of seabirds.

Audubon Alaska: You capture so many voices and shine a light on the issues surrounding Pebble Mine to show the devastating consequences it would have to Bristol Bay. Before we talk about the film, can you share a little about yourself?

Mark Titus: My name is Mark Titus. I’m a filmmaker from Seattle, Washington and an entrepreneur. I grew up here in the Pacific Northwest and began fishing for wild salmon when I was two years old with my Dad. I caught my first king salmon when he took me out to Sekiu, Washington and set me up with a little Snoopy Zepco rod from Fred Meyer, and he brought this 30 pound king up next to the boat, which I immediately tried to harpoon with my rod. It went down into the drink, never to be recovered, but what I got out of the deal was this deep love and fascination with and reverence for wild salmon and these creatures that keep coming back to give their lives so life itself can continue. The path that naturally took for me was growing up fishing for him and then in my college summers, I started going to Bristol Bay to work in the processing world of Alaska salmon as a product. Then in my twenties I spent a decade in Southeast Alaska working as a guide fishing for salmon in the Tongass National Forest.

Audubon Alaska: It sounds like Alaska is your second home!

Mark Titus: It is! Honestly, every time I get on a plane and come through the clouds and see the fjords and the islands and the Tongass itself, I have this big sigh and it feels like home. I lived out there for years and spent two winters caretaking the lodge that I guided for in the wilderness and I had some very, very quiet and reflective time in the wilderness that really was cement for my sense of home and my sense of purpose. I’m totally head over heels in love with these salmon.

In 2011, I read a book called Mountain in the Clouds by Bruce Brown and had a flash of realization about a man named Russ Busch who was a friend of our family’s who happened to be the attorney for the Elwha People for 40 years in an effort to remove two salmon-blocking dams from the Elwha River here in Washington State. I knew that Russ had stage 4 glioblastoma and likely wouldn’t make it for an entire year, and I knew I had to start filming him and his story. That led to my first feature documentary The Breach, which really was a full circle love story for wild salmon.

Audubon Alaska: In The Wild, you said, “The wild out there feeds the wild in me.” That was such a powerful moment and I was curious what that means for you?

Mark Titus: When I say that the wild out there feeds the wild in me, it really was a moment of awakening and a moment of remembering that I am a part of all this. It was very much an epiphany of "I’m exactly where I need to be,” and I’m a part of this thing that’s much bigger and greater than me. If I awaken to it, I can acknowledge it and I can be a part of this whole thing. So ultimately that line is a moment of awakening and remembering that the wild is our truest home and we are a part of it, we are not separate from it.

Audubon Alaska: When did you first hear about the Pebble Mine issue and how have you seen the problem evolve?

Mark Titus: I started going to Bristol Bay in 1991. When I was 18 years old and worked my butt off in a processing plant, I fell in love with the wilderness and the rough-hewn nature. There were no frills and it was hard, hard work. People were really weathered and wizened by this land. I was kind of all in on Bristol Bay, in particular, and Alaska.

Strangely enough, I ran a freezer line packing fish my last year there and I’d sit in the freezer room and I’d think about why am I doing all this? What is this whole exercise going to be worth down the line? I only came to realize later in my adult life this experience would help me in my advocacy work for Bristol Bay. I’d heard about it, ruminations and whispers about it, but like many people I became aware of it robustly after watching Red Gold, a wonderful film in 2007 by Ben Knight and Travis Rummel at Felt Soul Media. Those guys did an incredible job showcasing the country and why it’s so important. That lit a fire in me about this place I came to love many years before. Then, when 2011 rolled around, four years after seeing that film, I was considering what The Breach would be as a movie. Ultimately it became a big picture love story for wild salmon, but functionally it was an observation of what it takes to restore a system. Like the Elwha [River] that has 70 miles of habitat that was opened up by breaching two dams; it’s a wonderful story and a huge success that should be replicated all over the Lower 48. What it took [to restore the Elwha] was $350 million dollars and 40 years of effort by dozens of people and tribes and organizations. An insane amount of work and struggle went into this thing that almost didn’t happen. We compared and contrasted that with a place like Bristol Bay that’s still perfect, still pristine, and doesn't need any human management or interference because the habitat is still intact.

Audubon Alaska: The film connects viewers with your story and other stories shared within the film. How does your story intertwine with the story of Bristol Bay and what inspired you to tell this story?

Mark Titus: I went back to Bristol Bay in the summer of 2017 because I promised a Bristol Bay fisherman that I would come onto his fishing boat and tell his story. I almost didn’t go because I was so fresh into sobriety and I had gone through this traumatic experience. I didn’t fully understand that I was going to be filming something for an entirely new movie. It literally came down to that moment in the airport in SeaTac about to take off for Bristol Bay and I was like, “I don’t think I can do this. I don’t think I’ve got the stuff. I don’t think I have the courage and enough grit to do this thing.” And something outside of me (through a panic attack) said keep going, keep walking, keep doing this. It was a small, still voice. And somehow I was able to listen to it and get on that plane and go. It literally opened life back up for me. It came back to that moment: the wild out here feeds the wild in me. I wouldn’t have been able to experience it had I not decided to say yes to life, to say yes to going. Ultimately that’s my endnote on that. If there is ever a question, say YES and GO! Life will take care of the rest.

Audubon Alaska: That’s quite something, thank you for sharing! Can you talk about why salmon is so important for Alaskan communities and the world, and about salmon’s connection to our ecosystem and particularly the birds? Also, what’s your favorite bird?

Mark Titus: The realization of what my favorite bird happened in Bristol Bay. I was just 20 years old and I had a moment of clarity in Bristol Bay when I was standing on the bow of this fishing tender with a guy who was a mentor to me – his name was Uncle Lenny. I was looking at the grandeur and there were beluga whales going by when I said, “Geeze, I want to be part of all this so badly.” He looked at me and he said, “Hey, little brother, you already are. You just have to say thank you.”

So the very next night, I was standing on a ladder and painting the side of the fish plant preparing for the salmon season. It was beautiful, like 10 o’clock at night, and the sun was creeping down and these swallows were flying everywhere and dancing and sliding and jumping off rooftops. Taking in this whole scene with the river in the background, I was just absolutely full. Full of life and full of this wildness. I took Uncle Lenny’s advice and I said, “Thank you.” And literally, in that second a swallow flew by and clipped my ear with its wing. I had a realization after that my favorite bird on the planet are swallows because they dance through life so gracefully and they make their work an act of joy. And that became an inspiration for me to want to do the same thing for my life. To try to emulate and replicate swallows beautiful grace and joy that they move through life with.

That immediately wraps into the connectivity with salmon. When salmon return from the ocean, they bring in all the nutrients from the ocean with them. They are feeding over 130 different creatures, including swallows. The salmon come in and they spawn. [Then] they die and they rot and bugs come and feed on them. [Then] the insects feed on the carcasses and they feed the swallows and feed the system so everything works in harmony the way it’s supposed to. The salmon are this incredible engine of nutrients for this whole system to work efficiently. So, the swallows are directly connected to the salmon, directly connected to me and I’m just grateful for all of it.

Audubon Alaska: So how would Pebble Mine disrupt this delicate balance and what are some of the biggest concerns you have about the mine?

Mark Titus: When people think about the proposed Pebble Mine they automatically gravitate towards the most catastrophic outcome that could come out of a mine like that in a wilderness landscape like Bristol Bay. [However, the perceived] catastrophic outcome is a failure of epic proportions when the earthen dam that’s constructed is as tall as the Space Needle. [This dam will hold] back toxic effluent that has to be held in place and maintained forever, [and it could] burst either through an earthquake or a structural issue or another natural disaster. Then, that effluent goes downstream and it poisons everything in its path. The proposed mine site is in the headwaters of the most efficient and prolific systems inside Bristol Bay; the headwaters of the Kvichak and Nushagak at the top of Lake Iliamna that feeds these rivers. And as we know, gravity moves everything downhill.

What I’m equally or more concerned about is just by the very nature of permitting something like Pebble Mine, you are fundamentally and irrevocably changing the nature of Bristol Bay as a wilderness landscape. You’re taking something that’s pristine and unique in the world, frankly getting more and more unique by the day as we lose more habitat by the day, and you’re turning it into everything else that’s been touched by human encroachment in the Lower 48. In order to operate a mine like that you need to have roads, culverts, fuel, and engines moving to power this thing. By virtue of just letting this thing happen, you are creating an infrastructure that’s having deleterious effects on this habitat and pristine ecosystem that won’t ever go back. Once you let that genie out of the bottle there is not a chance it’s ever going back in. The mining industry in particular [would get] every last ounce of minerals that they can out of there because they’re beholden to their shareholders to do that. So what [used to be] a pristine salmon, bird, mammal, wilderness area that supports all of this life would be forever changed. And, if you want to break it down into just human perception, would you want to go visit a wilderness area that has a mine in the middle of it that has poisonous effluent leaching from it? Or would you want to eat your food that’s coming from the headwaters of such a thing? That wilderness designation is gone forever and if you look at the track record in the Lower 48, salmon runs have immediately and then irrevocably gone downhill. That’s what would happen.

Audubon Alaska: What did you learn from witnessing the cultural connection of Indigenous People to the area?

Mark Titus: It’s impossible to overstate the importance of wild salmon to the people of the Bristol Bay region who have lived and thrived there. Dena’ina, Yupik and Alutiiq people have been using the same methods and going to the same places for millennia. I most recently spent some time with the Wonhola Family at Lewis Point interviewing and featuring these folks in my new film The Turn. I had the great privilege of spending a day with them at their subsistence camp where they go to catch king salmon to feed their family for the year. I was with them when they put this fish up in the same traditional way they’ve been doing for generations. Drying it, smoking it and bringing it home to feed their extended family in New Stuyahok – the small village they’re from. It is a humbling experience to be present with people that have been present on this land for thousands of years and see it through their eyes and hear it through their words. The patriarch of this family that I’ve been interviewing, Tim Wonhola, did his interview in Yupik and spoke with deep reverence for the integral nature of salmon to all of their lives.

Audubon Alaska: When will The Turn be out and how can people watch it? What’s it about?

Mark Titus: The Turn is the third and final chapter in The Breach trilogy [and will be ready in 2024]. It completes a 15-year journey and a 15-year thought about wild salmon. [It captures what] I feel are the two most important actions we can do in our lifetime for wild salmon survival and resilience, which is to protect Bristol Bay and breach the lower four Snake River dams. The title of The Turn refers to the moment in time when wild salmon know it’s time to turn from the ocean and come home. Ultimately, I hope it refers to us as well as a species. We’re at a moment in time when we’re going to have to turn and make that chance to live in a way that is harmonious with the natural world that supports us or we’re not going to be around that much longer. It’s up to us, we can make that turn together. It feels like where there’s a murmuration of birds or school of salmon all turning at the same time, there’s a lot of people out there that are feeling this need to make this turn, too. The film is about documenting those people who are also turning over their life’s work to continue the survival of wild salmon into the future.

Audubon Alaska: What is the power of our voice and the power of community?

Mark Titus: This is a huge and important question. I created an impact brand and public benefit corporation called Eva’s Wild to address this exact thing. When I took my first documentary The Breach out into the world, we did a 25 city tour around the US.. At the end of each screening, there would be people that stayed after to participate in a Q&A session. Invariably, the first questions asked were, “What can I do to help?” and “How can I preserve Bristol Bay and salmon?” At the time, I said, “Write to your legislator and give to your favorite NGO.” Folks said, “I’ve done that, what else can I do?” And so what finally came into consciousness [with the help of] some friends who are in the wild salmon industry, was to [support] eating wild salmon from Bristol Bay. I decided that building a company that can house all of the things you can do for wild salmon in one portal was where I needed to go.

So I built Eva’s Wild, which is the word "save" backwards. The name of the boat I was on while filming The Wild was also named the F/V Ava Jane. This was the inspiration for it. Ultimately it’s designed to empower people to do the only three things we really got. When people are disenfranchised about being able to take meaningful action, it’s important to remember we’ve got our vote, our dollar, and our voice. It’s super important to use all three. Go to vote when it’s time to vote. Be aware of the candidates that are supporting wild places that will sustain wildlife like birds and salmon for generations to come. Use your dollar. And that’s where Eva’s Wild comes in. I link wild salmon directly to people’s doors across the United States from Bristol Bay. 20% of our profits go to Indigenous-led efforts in Bristol Bay to protect that place. And third, use your voice. Join our community. Join the National Audubon Society. Use your platform - whether it’s social media or your kitchen table. At the National Audubon Society, you have a community of experts with deep roots and deep ties to advocacy to make a difference where it counts. And it does work. But, you’ve got to show up. Like Bella Hammond, the former First Lady of Alaska said, “You’ve got to keep using your voice. You’ve got to keep banging the drum. You’ve got to keep doing it over and over again.”

It doesn't happen overnight but it does happen if you’re persistent. When you find your people or you find your school of salmon… what a joy! What a privilege!

Do it. Be involved. If you take that step, like that step for me was saying yes to get to the airport, and you go and you do it then doors will open up. People will appear. Things will happen. It really is a beautiful thing that life wants to continue to flourish. Life begets life.

__________________________________

Watch The Breach and The Wild for free today and sign up to receive newsletters from Mark Titus here. You can also follow Mark on Instagram @augustisland, Eva’s Wild @evas.wild and The Turn @theturnfilm.

For additional viewing, check out Mosaic: The Salmon Wilderness of Bristol Bay, AK produced by the University of Washington’s Alaska salmon program with cinematography by Jason Ching who is a scientist and contributed to the breathtaking aerial footage in The Wild.