While the Trump Administration’s Executive Order “Implementing an America-First Offshore Energy Strategy” (April 28, 2017) called for expanding offshore drilling in the Arctic, the limits to offshore development in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas are clearly recognized. This section from Audubon Alaska’s forthcoming Ecological Atlas of the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas outlines the limitations to offshore development in the Arctic.

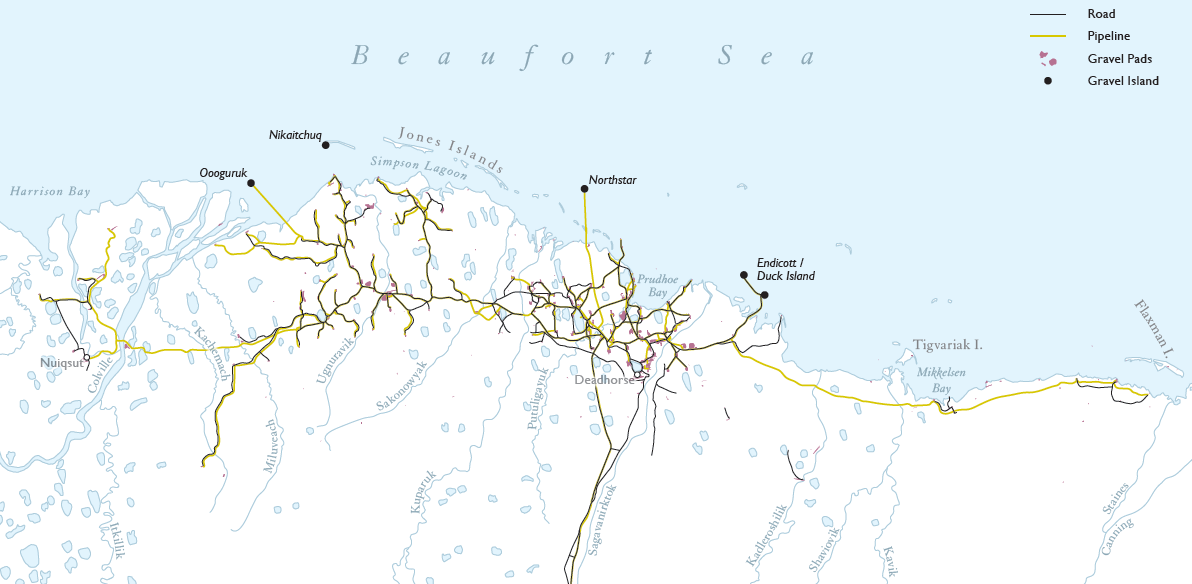

Excluding Prudhoe Bay (see map), Alaska’s Arctic is not a mature petroleum province in terms of geological understanding or infrastructure. Offshore areas remain firmly on the frontier. The primary factors limiting industrial development in Arctic waters include sea ice, the challenges of deep-water engineering, regulatory structure, barrel price forecast, and port infrastructure. Furthermore, unsolved engineering challenges (for example, the wreck of the Kulluk) can give investors cold feet in a hurry.

Sea-Ice Limitations

Operating in areas where open water conditions persist for less than 90 days of the year are considered theoretically workable, regardless of water depth. Gravity-based rig structures (GBS) are proven solutions for drilling in depths shallower than 330 feet (100 m), while ship-based drilling and subsea tie-back configurations are proven for greater depths.

The technological frontier exists in waters where ice-free conditions persist for less than 60 days, and water depths reach deeper than 330 feet (100 m). Research breakthroughs are needed for engineered structures in waters with a year-round ice cover. Spill containment systems for these remote, ice-covered waters remain in the research stages.

Water-Depth Limitations

Water depth alone is not a controlling factor on ocean drilling. Bottom-resting (jack-up type) drilling platforms are routinely used in shallow, nearshore areas and lagoons of the Canadian Beaufort Sea coast, where water depths are less than 330 feet (100 m). In the Gulf of Mexico, offshore drilling is taking place in waters deeper than 3 miles (5 km). Deep-water platforms are mature technologies in sub-Arctic oil basins around the world, but remain unproven in the US Arctic, although Norway and Canada have operated Arctic platforms for years. The structural upgrades required to operate in Arctic waters are not generally viewed as limitations, but the increased up-front costs of customized equipment may be a limitation in certain barrel-price environments.

Regulatory Limitations

In the US, there are 27 separate agencies involved in the planning and permitting process for the US Outer Continental Shelf. Permitting involves six steps: leasing, seismic acquisition, site selection, stakeholder engagement, exploration drilling, and development/production planning (National Petroleum Council 2015). The US Department of Interior has primary influence over US domestic oil-and-gas policy, but the multinational Arctic Council lends input, along with several other working groups and coordination bodies

Barrel Price & Investment Limitations

Petroleum is a global industry governed by global economic forces: supply, demand, international politics, and investor confidence. The reasons why major oil companies choose to explore for and develop offshore oil leases are many, but two factors outweigh all others: short-term barrel price and long-term price forecasts. Price drives investment. Investment capital puts people and equipment in the field. Price is such a dominant factor that when it dips below a certain threshold, development of the reservoir simply stops: production activity is cut back, employees are laid off, and rigs shut down. Conversely, inflated price environments cause field boundaries to expand to encompass marginal areas previously considered uneconomic.

Other factors that influence decisions to invest in offshore projects include shareholder concerns, military events, major accidents, lease sales, technical limitations, regulatory delays, shifts in corporate tax rates, and legal pushback from the environmental community. Oil companies, like multinational shipping and mining companies, operate on very long timelines (planning spans decades). These companies are financially stable, influential, and patient.

Price stability around $80 per barrel (in 2016 dollars) is a strong positive signal for companies considering entry/re-entry of Arctic leases. Currently, there exists high uncertainty in the price outlook. This, coupled with a broad expectation that threshold barrel prices (around $80/barrel) will not return any earlier than 2020, is currently suppressing investor interest in offshore Arctic projects.

Port & Infrastructure Limitations

The Arctic Ocean is remote and harsh. Long transport distances exist between offshore fields and industrial ports. Long distances multiply supply chain transportation costs and introduce delays. Currently, no deep-draft ports capable of servicing offshore production exist along the western coast (Chukchi Sea) and northern coast (Beaufort Sea) of Alaska, a distance of some 3,000 miles (4,800 km).

Likewise, no suitable ports are present on the Russian Chukotka Peninsula. Connections between seaports and overland transportation networks are a significant limitation to offshore oil development going forward. In general, major overland routes (rail, road), common in the Lower 48 US states and Canada, are rare in Alaska and the Russian Far East. Basic marine navigational infrastructure in ice-free corridors of the Chukchi-Beaufort Seas region is another deficiency.

A recent study by the US Army Corps of Engineers (US Army Corps of Engineers and Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities 2013) identified four candidate locations for future development of deep-draft port facilities and associated infrastructure. Nome and Port Clarence were the top two choices, with Cape Darby and Barrow also short-listed. Construction of one or more Arctic ports large enough to accommodate offshore production that would serve as a transportation hub, a repair and resupply center, and house industrial-scale safety vessels is at least a decade away.

The Ecological Atlas of the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas, due out in July 2017, a comprehensive, transboundary atlas that represents the current state of knowledge across many Arctic marine subjects. Human uses in the Arctic are covered extensively, such as subsistence, commercial fishing, oil and gas development, and vessel traffic.